(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 28 September 2016.)

Why have property prices risen steadily since 1984, punctured only by the Asian financial crisis and the ensuing recession of 1997-2003?

There are three explanations, two are demand side factors and the third is a supply side factor.

First, demand is driven by inflationary and deflationary pressures originating from business cycles abroad, including Fed policy, and mediated primarily through their effects on interest rates and exchange rates.

Second, China’s opening has generated two positive effects on demand. The first effect stems from the structural transformation of the Hong Kong economy away from manufacturing into services that precipitated price inflation in domestically consumed services (including residential property price inflation). The second effect is an increase in demand from the inflow of immigrants through cross border marriages and the rising wealth of mainland buyers.

Third, the slow process of land development and housing construction has reduced housing supply growth. There are two interpretations as to why that has happened.

One is the populist view of the man in the street that blames “government-developer- landlord” cronyism. Critics of government have often made such charges of conspiracy. They allege that government is doing the bidding of developers and landlords to purposely reduce supply so as to boost prices. It is a charge advanced by a growing number of opposition politicians. Alice Poon’s Land and the Ruling Class in Hong Kong (2005) made similar allegations but failed to substantiate them. This explanation is unconvincing because it depends on proving why cronyism has risen over time and whether its timing coincides with rising housing prices.

Another view is that planning and building regulations have delayed development and housing supply. Such regulations have grown and become more onerous over time. The opening up of the political system has also introduced more uncertainty into the development process and delayed it further. A more demanding set of regulations is also more vulnerable to being held hostage to interest groups and politics by delaying the decision making process.

Regulatory costs have received great emphasis in the economics literature as a cause of the slow growth of housing supply in major cities in the world. Harvard economics professor Edward Glaeser was the first to identify planning and building delays as the most important cause of the delayed supply of housing.

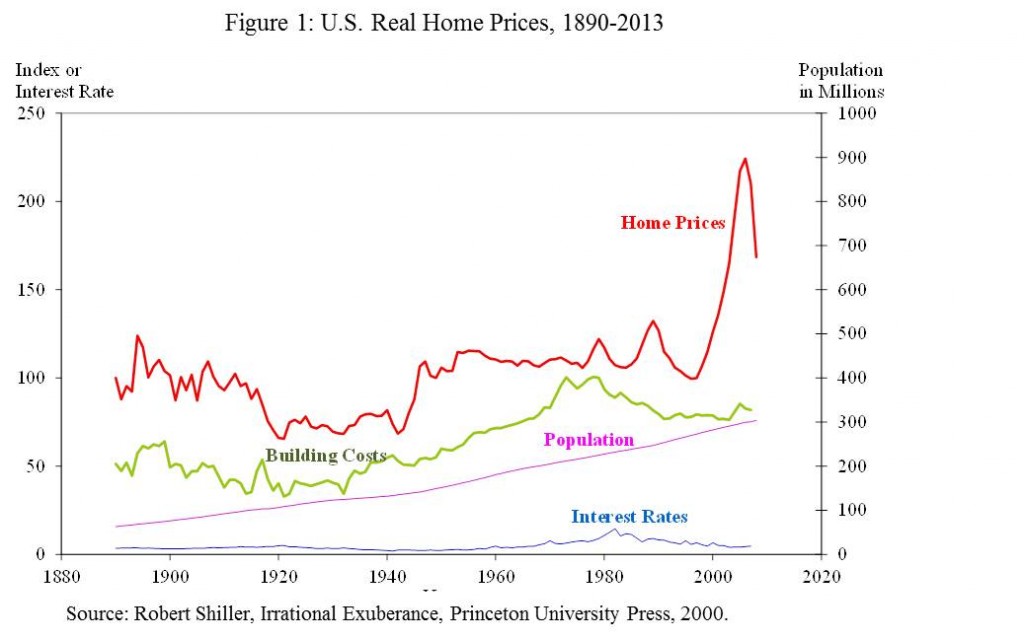

Glaeser set out to explain why housing supply across most cities in the US had failed to respond to the rising housing demand in the mid-1990s. Yale economics professor Robert Shiller attributed it to irrational mass psychology and easy credit. According to Shiller’s own data, real home prices for single family homes in the US had remained stable from 1890 to the mid-1990s, except for the period before the Great Depression until the end of World War II (see Figure 1). Why did real housing prices start to surge after the mid-1990s? This was a big puzzle for Glaeser, who wanted a better explanation for the unusual surging of home prices than Shiller’s story.

Glaeser presents evidence to demonstrate how restrictive regulation constrains the supply of housing so that increased demand leads to much higher prices, not many more units. This pattern is found in all the high price housing markets across the United States, but absent from those areas with more relaxed regulations.

In a series of path breaking studies beginning in the early 2000s, he showed that zoning and building restrictions had enormously delayed development and housing supply. Home building is a highly competitive industry with almost no natural barriers to entry in New York City, yet prices in Manhattan appear to be more than twice their supply costs. Glaeser argued that land use restrictions are the natural explanation of this gap.

In Boston, housing supply is not keeping up with demand. In the 1960s, there were 172,459 new units permitted in the Boston metropolitan area; and in the 1980s, 141,347. However, despite the sharp rise in prices in the 1990s, only 84,105 new units were permitted in that decade. The decline in permits has been particularly striking for units in multi-family buildings. In the 1960s, less than 50 percent of all permits in the Boston metropolitan area were for single-family homes. In the 1990s, over 80 percent of all permits were for single-family homes. Land saving plot ratios had therefore been effectively reduced.

There is little evidence that Boston is running out of land. The problem is that developers face an incredibly heterogeneous set of local regulatory regimes. These include minimum lot size regulations, prohibition of irregularly shaped lots, growth caps and phasing schedules, wetland regulations, septic-system regulations,subdivision rules, and so on. Meeting these regulatory costs was estimated to be 20 times more than land costs.

By contrast, housing prices in Tokyo have not grown in 20 years. Tokyo adopts a laissez-faire approach to land use that allows lots of construction, subject to only a few general national regulations. In 2014, there were 142,417 housing starts in the city of Tokyo (with a population of 13.3m and no empty land) compared with more than the 83,657 housing permits issued in the state of California (with a population of 38.7m) and 137,010 houses started in the entire United Kingdom (with a population of 54.3m).

How is this possible? Japan has a history of strong property rights subject to zoning rules. In fact, Japan’s constitution declares “the right to own or to hold property is inviolable.” A private developer cannot make you sell land; a local government cannot stop you using it. What you build is strictly your business. But this alone cannot explain everything.

Japanese urban planning institutions were originally based on western models similar to the US system. Cities were zoned into commercial, industrial and residential land of various types.

From 1986 to 1991, Japan lived through a massive property price boom and bust crunch. In the aftermath, Japanese economists were decrying planning and zoning systems as major contributors to the problem because they reduced supply. The government listened and overhauled its system by reducing regulation and speeding the permit approval process, in part to help the economy recover from a bubble.

In commercial areas in Tokyo, you can build what you want. Apartment towers have appeared in former industrial zones around the bay. Hallways and public areas are excluded from the calculated size of apartment buildings, letting them grow much higher within existing zoning, while a proposal now under debate would allow owners to rebuild on a larger scale if they knock down blocks built to old earthquake standards.

If it hadn’t been for the regulatory reform, Tokyo would have had the same regulatory rigidities that Boston, New York City, London or San Francisco are still burdened with. Instead, Japan completely escaped the boom and bust crunch of the Western economies prior to 2008.

Glaeser has shown that over the period 1996 to 2006 (when the US market experienced a long housing price boom), interest rates accounted for no more than one-fifth of the rise in house prices. Easy credit could not be the most important explanation for the housing price boom. There was also no evidence that approval rates or down payment requirements could explain most or all of the movement in house prices.

Regulatory rigidities in development and housing supply are the most significant factors contributing to housing bubbles. Rising housing prices are not an inevitable consequence of growth and fixed land supplies — rather, they are the result of policy choices to restrict land development and housing construction.

Allowing housing supply to respond to rising demand is essential for equity and equality. Housing price booms produce huge distortion effects by setting young against old, redistributing wealth to the already wealthy, and denying others the chance to move to cities where there are good jobs.

A widely cited study by Chicago economics professor Chang-Ta Hsieh and Berkeley economics professor Enrico Moretti has shown that high housing prices in cities like New York City, San Francisco, San Jose and others reduce population inflows into areas of high productivity and result in lost opportunities for economic growth. They estimated that high housing prices cost the US economy US$1.95 trillion (or 13.5% of GDP) in lost wages and productivity in 2009. This would amount to an annual wage increase of US$8,775 for the average worker.

In Hong Kong, the slow conversion and redevelopment of industrial buildings to meet other uses has contributed to rising residential property prices. Reports of industrial units being subdivided into residential units without permit reflects a deep regulatory failure – not of preventing conversion, but of failing to facilitate proper conversion. Zoning restrictions and the slow and uncertain process in facilitating change is at the core problem of the restrictive regulatory regime.

The increasing hostility against approving higher plot ratios for developments in urban areas due to environmental concerns and against constructing public rental housing estates because of a “not-in-my-backyard” (NIMBY) mindset have further delayed conversion and redevelopment. The present arrangements are half transparent and half opaque. The process is so open-ended that the only outcome is maximal uncertainty. This is what is responsible for almost stopping the conversion and redevelopment process.

Most of the undeveloped lands in Hong Kong are in the New Territories under Block Government Lease as agricultural land. In the famous case of the Attorney General v Melbado Investment Ltd. [1983] HKLR 327, the Court of Appeal ruled that the designation of agricultural land was mere description and did not limit its use to agriculture only. The land can be used for other purposes with permission as long as buildings are not constructed on the agricultural land.

The redevelopment of agricultural land has been under planning control since 1991 under the Comprehensive Development Areas (CDAs). Successful development, however, depends on agreement between rural landlords (who are descendants of indigenous villagers), property developers, and rural squatters (who have been living on agricultural land with some engaged in farming activities). The involvement of government officials in the negotiation almost guarantees the process will be drawn out for years if not decades. Most of the lands are also small fragmented plots that make negotiation even more complicated. The interests of different stakeholders are difficult to align through negotiations alone.

With such diverse interests, the situation of land development in the New Territories is truly a “tyranny of the status quo”. This status quo has been made more difficult by the rising value of agricultural land put to alternative uses. The first significant commercial use was an open parking area for container boxes. Subsequently the lands have also been used as parking areas for cars and trucks, collection sites for recycled product, storage areas, etc.

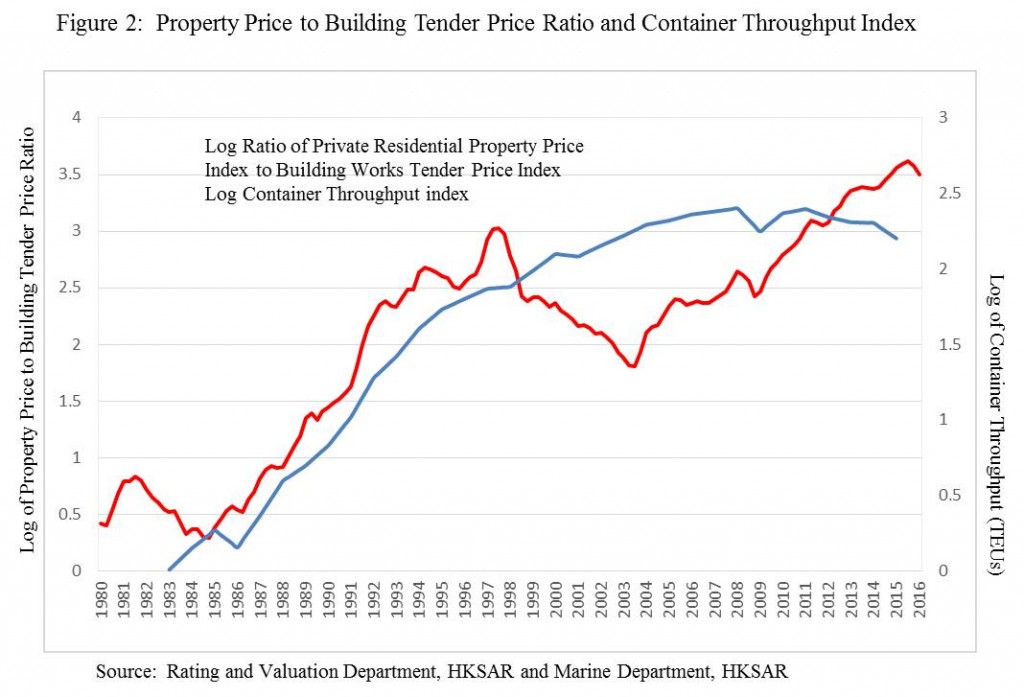

It is interesting to note that the percentage excess gap of residential property prices above construction costs soared within a short few years after the number of container boxes discharged at our terminals started to takeoff in the mid-1980s (see Figure 2). This is solid empirical evidence that the regulatory cost of redeveloping land has been rising. It coincides with the rapid rise of container throughput in Hong Kong, which rose from the mid-1980s until peaking in 2008, when world trade growth also began to slow down.

It is not at all surprising that the regulatory cost of redevelopment started to rise in the late 1980s, when agricultural land in the New Territories increasingly became the most important source of land supply. Given the great difficulties of coming to a mutually agreeable settlement over the alternative uses of agricultural land, one could have easily predicted that property prices could not fall.

With the increasing divisiveness in politics after 1997, the focus soon became one of finding someone to blame for high and rising residential property prices. In a city where half the population owns property and the other half does not, this will always be a highly charged political issue – restrict supply and prices soar, relax supply and prices collapse – can there be a winning strategy?

The first chief executive C H Tung was blamed for precipitating the collapse of property prices on account of his policy to build 85000 housing units each year and eventually lost his job. The second chief executive Donald Tsang left office roundly blamed for failing to increase the supply of land and housing and allowing property prices to takeoff. The third chief executive is feverishly trying to negotiate land deals to boost housing supply case by case to the loud clamor of angry have-nots.

The real challenge is to find another strategy that would lower regulatory costs in order to get out of this situation quickly for otherwise political polarization will exacerbate.