(This essay was published in South China Morning Post on 12 April 2017.)

The most important source of growth in housing demand that has not been foreseen in Hong Kong is the rapidly escalating number of divorces and remarriages. This demand has meant many young adults cannot find affordable homes to set themselves up and start families, with the result they have grown increasingly frustrated.

Hong Kong today has the fifth highest divorce rate in the world. Divorces and remarriages accelerated after China’s opening, which eased social interaction and led to an explosion in the pace and scale of cross border marriages.

One can literally read the pressure on housing by looking at the divorce and remarriage rates, which leapt from 84,788 divorces and 65,794 remarriages from 1976-1995, to 323,298 divorces and 256,066 remarriages from 1996-2015. Total marriages increased only from 803,072 to 878,552. At the same time, housing production between the two periods dropped by one-third.

The significance of divorces and remarriages for public housing policy is that these are mostly concentrated in the bottom half of the income distribution and are putting pressure on the growing waiting list for public rental housing.

Public rental housing allocation policy does not distinguish between first-time marriages and remarriages. So there is an implicit incentive to divorce and remarry for those without means. Unless this incentive is removed, then building more public rental housing units would only fuel demand by subsidizing divorce and remarriage. Public housing policy has to be reviewed if it ever hopes to succeed in meeting the increasing housing demand among those without means.

Instead of building more units, public housing policy should focus primarily if not exclusively on homeownership as a benefit that would be provided once in a lifetime. This would provide a serious disincentive among beneficiaries to breaking up the family.

Homeownership could be achieved by selling public housing units to existing tenants, especially those units built since 1997 and the stock of units still on the Tenant Purchase Scheme list. In one fell swoop, this would create a serious disincentive against divorce among households in the public rental-housing sector. And it would take a big step towards reducing the economic divide.

Another argument in favor of privatizing rental units and increasing homeownership is related to fiscal benefits and economic and social development.

Hong Kong has increasingly financed its economic and social programs largely from land and property values. The latter have been securely protected by common law and supported by the high economic growth rates in the Asian region.

This is unlikely to change in the near future. Revenues from salaries tax are unlikely to increase given the declining rate of growth of real wages and human capital in the workforce. The latter can be improved through education but it will take years if not decades to have an impact.

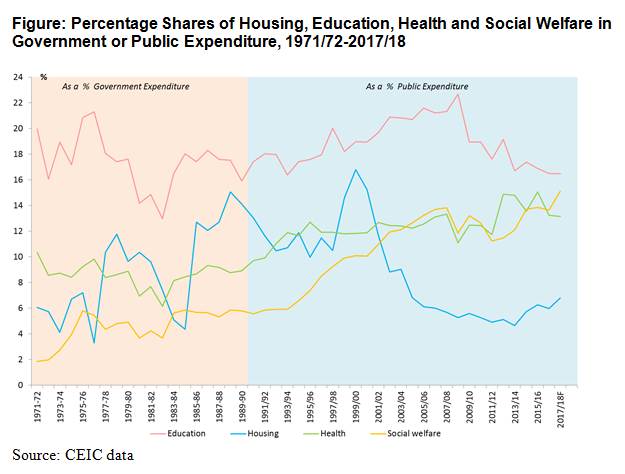

At the same time Hong Kong is facing likely large increases in health, education and social welfare spending over the coming decades. Over the past two decades, their growth has been accommodated by declines in public housing expenditure. Overall government spending has therefore remained as a constant share of GDP. But if we were to build ever more non-revenue generating rental units then public housing expenditure will quickly rise and the present fiscal balance will rapidly erode.

Under these circumstances, reforming how we finance public housing offers the only real hope of balancing fiscal budgets in the future and providing adequate funding for investments in education, health care and social welfare for realizing a better future. The huge fiscal surpluses of the past years were merely the windfall gains of an unforeseen property market boom and cannot last forever.

In today’s market, even the middle class cannot afford to become homeowners. They too have become a responsibility of the public purse, albeit inadvertently. Today eighty per cent of the households have incomes below the official eligibility level to qualify them for Homeownership Scheme flats.

If we reform our public housing policy into an affordable ownership program for the ‘have-nots’, then we will create an opportunity for both public housing tenants and the government to recover the lost values of the land used for public housing – ‘lost’ because there is no alternative use. This is the only approach that can simultaneously provide a solution for our future budget challenge and allow the present ‘have-nots’ to become homeowners without the need to commit any new resources.

And what a lot of value they represent. The entire stock of existing public rental housing units (excluding Tenant Purchase Scheme units) evaluated in 2016.Q3 prices was HK$2.95 trillion dollars, and most of this value is attributable to land. Today it is certainly even higher after the recent surge in property prices.

Next week I will look at how we should reform our public housing policy to reunite a divided society, renew our faith in our fiscal foundations, and hopefully amend our polarized politics so that our economic future will not be held hostage again and again.