(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 26 October 2016.)

As the 2016 US Presidential election campaigns unfold as a surreal train wreck, the obvious question is how did the Republican Party wind up with Donald Trump as its nominee?

Is there a logical and empirical explanation for Trump’s rise? Is this a sign of rising economic inequality? Or is it growing racism and xenophobia? Or of democracy gone wrong?

The first time I realized that Trump was likely to become a serous contender was when The Economist drew attention to the threat he posed and called upon the political heavies of the Republican Party to stop him. They failed to do so despite their dislike of Trump and what he represented.

Trump’s campaign platform draws from a history of presidential aspirants focused on immigration and international trade. In 1992, Pat Buchanan sought the Republican presidential nomination and Ross Perot ran as an independent presidential candidate (and won 19 percent of the popular vote) on a similar mix of populist positions.

Both Buchanan and Perot ran again in 1996, with Buchanan winning the New Hampshire primary and Perot winning 8 percent of the popular vote under the banner of the new Reform Party. Most of Perot’s supporters were originally Republicans who later returned to become more active participants in Republican politics. These candidates paved the way for Trump’s first campaign in 1999-2000.

Trump failed in his first presidential bid to Pat Buchanan, when they both competed to be the Reform Party’s presidential nominee in 2000. Trump bowed out rather than face certain defeat when it became obvious that he would lose. Buchanan’s constituency also turned out to be mostly Republican voters. Trump then sat out three presidential cycles after considering runs in 2004 and 2012.

But his 2000 presidential bid taught him that many disaffected anti-establishment voters had racist, anti-immigration, and nativist attitudes. They eschewed cosmopolitan elitism and blamed trade and immigrants for their economic woes.

Several aspects of that campaign should be familiar to observers of the current campaign cycle. Trump is still committed to self-funding, complains of foreign countries ripping off America, and his key communications strategy is to appear in the media a lot. Trump has successfully earned six times the media coverage of any other Republican candidate in this cycle. But one aspect of Trump’s campaign is decidedly different this time around.

In 2000, Buchanan ran an election campaign focused on opposition to immigration and support for “America First.” Trump declined to pursue a nativist appeal back then. In fact, he repeatedly accused Buchanan of racism, calling him a “neo-Nazi” and “Hitler lover,” who had systematically bashed blacks, Mexicans and gays.

In an op-ed following his withdrawal, Trump touted his campaign as “the greatest civics lesson that a private citizen can have” but also said he “saw the underside of the Reform Party.” He mentioned meeting earnest reformers as well as a host of odd conspiracy theorists. Yet by the time Trump announced his candidacy for president in 2015, he had become the most prominent spokesperson for these conspiracy theorists thanks to his long push for Obama’s birth certificate.

In 2000, Trump learned of the disaffections of the Reform Party’s constituency. This time, Trump has retained Perot’s anti-trade and anti-elitist messages but added Buchanan’s warnings of losing the country to ethnic and religious minorities, and he led from the beginning to win the Republican presidential nomination.

In 2016, race and identity has emerged as the principal dividing line in American politics, not economics (despite some strong trade and China-bashing rhetoric). Though race has always lived close to the surface of American politics, it has rarely been so explicitly front and center in political campaigns. So how did this happen?

Trump is not acting in a vacuum. He is instead riding forces set in motion a half century ago. His identity-based nomination should be seen as the logical culmination of Republicans’ 50-year “Southern strategy” to make politics primarily about race and identity instead of economics. This was a winning strategy first tried by Richard Nixon in 1972 and with greater success by Ronald Reagan in 1980.

For Republicans, the irony is that this identity-based strategy reached its full maturation with Trump at precisely the moment when it is no longer a winning strategy because American demography is shifting in favor of ethnic minorities. For Democrats, with their coalition increasingly split along class lines, identity is looking more and more like the only issue that can keep the party coalition together. And this is the issue on which Hillary Clinton is now hitting Trump hardest.

Politics involves many issues, across multiple dimensions. But in a two-party system, there can only be one principal dividing conflict at any given time. The fight over this dividing line is the most important fight in all of politics because it determines which party is in the majority and which party is in the minority, and which issues get argued about between the parties and which issues get argued about within the parties.

Public opinion, however, does not exist on a single dimension; any alignment contains within it multiple disagreements, which tend to grow over time. But throughout most of American history, there have been essentially two main divisions in politics: one over economic policy (essentially: more or less government intervention in the economy) and the other over social and cultural identity issues.

The first relates to arguments over the appropriate distribution or redistribution of economic benefits to the less fortunate. The second, to American values.

Mass opinion surveys have revealed that the beliefs of most people on these two issues tend to be poorly correlated. Most voters are not ideologues. Knowing their views on government regulation of business will tell you very little about, say,their views on abortion (except for maybe the 10 to 15 percent of respondents whose economic and socio-cultural values are ideologically tied together).

It follows that a politics organized around abortion could look very different from a politics organized around business regulation. To illustrate, let us suppose the Democratic Party is pro-choice on abortion and pro-regulation on business, and the Republican Party is pro-life on abortion and anti-regulation on business.

If, say, 60 percent of voters are pro-choice and 60 percent are anti-regulation, the Democratic Party wants voters to make abortion the No. 1 issue in an election. The Republican Party wants voters to make business regulation their top issue.

Whichever party is successful in making their favored issues the focus of the election wins the majority. Parties generally lose when they are forced to choose between public opinion (supported by 60% of the voters) and their stated position (supported by the other 40%) because the principal dividing line of politics forces them to do one or the other.

From 1800 to 1856, economic policy defined the primary dividing conflict. The Democratic program of agrarian expansionism (also known as the Jefferson and Jackson program) won almost every presidential election against the Republicans except in 1840, because the nation was mostly farmers.

From 1860 to 1928, the Republican economic program of commercial and industrial development won every time. Abraham Lincoln defeated the Democrats decisively in 1860 when he split their agricultural voter constituency by making race the top issue through his advocacy of abolishing slavery. This also plunged the nation into civil war.

The path leading to Trump begins in 1932, when Democrats formed a majority coalition that included Northern progressive liberals and Southern conservatives. The Great Depression had made economics the fundamental dividing line of conflict. And with Republican President Herbert Hoover getting the blame for the collapse, Democrats were on the winning side of the issue.

Dwight Eisenhower, who became Republican president in 1956, attempted to move the party to become a New Deal party but was unsuccessful as the party heavies and their supporters still wanted to undo the New Deal and felt sure that public opinion would move to their side.

From 1932, the Democratic economic interventionist program won most of the time until the civil rights constitutional amendments in 1966 created a backlash that made race an emerging political issue once again. A realignment of voters gradually took place. When the conservative Barry Goldwater lost in 1964, it finally became clear the Republicans could not win purely on limited government as a defense of liberty. The Republicans needed a second issue to split the Democratic Party once again, just as Lincoln had done in 1860.

The Democratic majority from 1932 to 1964 had always contained an internal conflict between Northern progressive liberals and Southern conservatives over civil rights. When Northern progressive liberals became the dominant voice and passed a series of civil rights laws, this created a backlash among Southern white Democratic conservatives and Northern working-class whites. The latter were directly affected by urban riots, and housing and school desegregation.

The Democrats failed to speak to the urban riots and segregation, or to acknowledge some of their own hubris in exercising power, through Ivy League-educated leaders, to solve deep social problems. Their 1972 presidential candidate, George McGovern, was labeled as the candidate for “acid, amnesty and abortion” and it stuck.

Many former Democrats were driven to the Republican Party. And with that, the Democrats effectively lost their winning political majority. This gave Republicans the cross–cutting issue with clear majority backing that they needed. Under Nixon’s strategic guidance, Republicans went full steam ahead in making race and identity the principal dividing line in American politics.

With Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, Republicans solidified a winning coalition around a platform of “limited government” beyond economic issues. These issues were wide-ranging.

The private lives of citizens should not be meddled with to enforce some Ivy League intellectual’s idea of racial justice, nor should middle-class taxpayers be asked to foot welfare support. Everything government tried to do, from regulate business to provide free school lunches was interfering with the free market and with liberty.

Economic and socio-cultural values could be ideologically tied together in a Cold War era because Communism had to be faced down as the enemy of both capitalism and Christianity. So Republicans were the natural home of traditional Christians compared to progressive liberal, abortion-loving Democrats.

This winning political coalition had internal conflicts, too. Many of the economic non-interventionists (who were libertarians and cultural cosmopolitans like Milton Friedman) and many of the cultural conservatives (who were former New Deal Democrats who supported universal social and medical entitlements) had little in common, other than feeling they did not belong to the Democratic Party (though for different reasons).

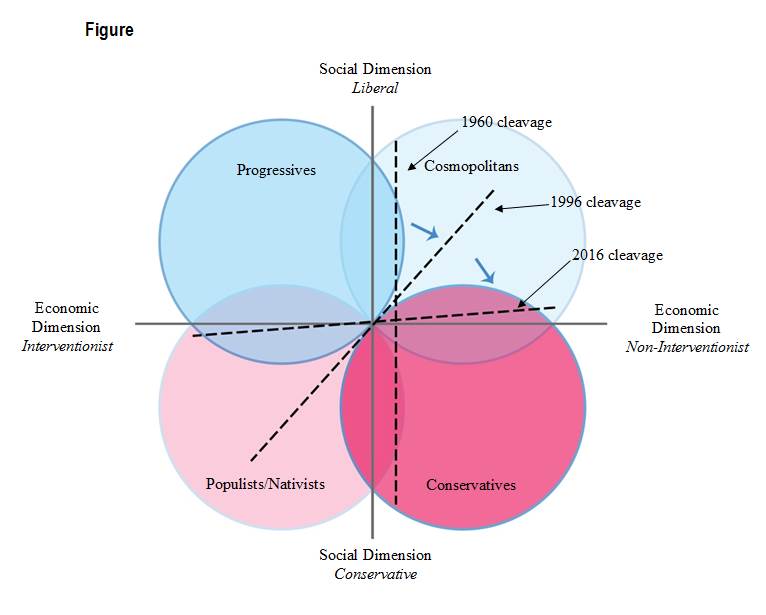

This basic narrative is nicely summarized in a diagram created by political scientist Scott McClurg (2016), which I have slightly modified. It shows how the central dividing line in American politics has rotated clockwise from 1960 to 2016. At the start in 1960, the major cleavage was over economic issues with the Democrats commanding a majority favoring interventionist policies and the Republicans opposed to it. By 2016, the major cleavage has become social and cultural issues with liberal progressive and conservative values in conflict.

The Progressives (Al Gore, Walter Mondale, Jimmy Carter) were social liberals and economic interventionists. The Cosmopolitans (Pete Wilson, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Nelson Rockefeller) were social liberals but economic non-interventionists. The Conservatives (the Bushes, Ronald Reagan) were social conservatives but economic non-interventionists. Finally, the Populists/Nativists (Pat Buchanan, George Wallace, Huey Long) were social conservatives and economic interventionists.

Beneath the shifting majorities was a significant cross-party swapping of voters. Democrats sent Republicans their non-college educated, culturally conservative white voters, mostly in declining rural and urban areas, who had been the core of the New Deal. In return, the Democrats got culturally liberal wealthy professionals, largely in prosperous urban and suburban areas, many of whom were “Rockefeller Republicans” and had once opposed many elements of the New Deal. For example, between 1992 and 2012, the Republicans did increasingly better in elections in the less-educated states, while the Democrats did increasingly better in highly educated states.

But the Republican future was not secured. America was steadily becoming more ethnically diverse and more educated. The younger generation was more culturally and socially liberal than the previous generation. Republicans might have been converting more Democrats to their side than vice versa. But Democrats were making greater gains among new voters, and also doing better among wealthy cosmopolitan Americans. Although the 1972 Democratic coalition of social liberals and economic interventionists was a losing one, in 2008 it was a winner.

Another problem for the Republican elites, whose vision of “limited government” was more rooted in economic non-interventionism than cultural conservatism is that since the mid-2000s, they have become more and more a minority within their party. The party has become more dependent on conservative working class whites to win elections.

Moreover, the majority support for the the Republican Party comes from rural and declining urban areas, which are slowly dying. These voters have no interest in the Republican priorities of voucherizing Medicare and privatizing Social Security. They want their entitlements and they want government to do more for old people and the middle class. The Republican Party has become less a party of business and enterprise, and more one of the declining middle class. This same group is also really concerned about immigration.

Between 1990 and 2014, the share of foreign-born citizens in America went from 7.9 percent to 13.9 percent. The last time the proportion was this high was 100 years ago, when it provoked enough nativist backlash in the 1920s to largely close the border for four decades, until 1965. The rising tide of immigration has indeed provoked backlash, which has been channeled into a Republican Party now increasingly dependent on conservative white voters for support.

Indeed, pro-Republican states have seen a much greater percentage increase in immigration than pro-Democratic states. Of the 24 states that the Republican candidate Mitt Romney won in 2012, 18 were states that had experienced more than a doubling of immigration after a history of low immigration. Political scientist Dan Hopkins (2010) has found that a sudden increase in the number of immigrants is the most powerful predictor of which localities will consider anti-immigrant ordinances.

Obama’s election in 2008 was initially viewed as a landmark of progress in race relations, but it also triggered a racist backlash. Political scientist Michael Tesler (2012) found that whites with strong racist attitudes turned much more sharply Republican subsequently, including some who had previously been Democrats.

Democrats have felt increasingly confident they can win national elections with the “Obama coalition” of racial minorities and white liberals. They now have fewer reasons to moderate their views on racial and social issues, and they have taken strong stands on same-sex marriage. Given all this, socially conservative whites have become further convinced their country is being taken from them.

Interestingly, the economic divide within both the Republican and Democratic Parties has also widened. The Republican Party is now in open warfare between Trump supporters and the NeverTrumpers. Democrats are less divided, but internal rifts between Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders mirror an “establishment” versus “insurgent” conflict that is also real and likely long lasting. This makes it difficult for either party to successfully mount any economic policy without the cooperation of the other party.

Whether there will be space left for cross-partisan cooperation to make the political system function remains to be seen. One cannot be optimistic about the prospects.

Over the past 50 years, the split among voters along partisan lines has reached historic levels. A large number of issues that were once non-partisan or non-ideological have become partisan ones.

There is little reason why race and identity will not remain the dividing line in American politics for a while to come. The Democrats see it as a winning strategy. And the Republicans will not be able to ignore the majority voices of its supporters now that Trump has opened the Pandora’s box.

References

Hopkins, D J. “Politicized places: Explaining where and when immigrants provoke local opposition.” American Political Science Review 104, no. 01 (2010): 40-60.

McClurg, S D. “The clockwork rise of Donald Trump and reorganization of American parties.” VOX, Mar 14, 2016.

Tesler, M. “The Return of Old-Fashioned Racism to White Americans’ Partisan Preferences in the Early Obama Era.” The Journal of Politics 75, no. 1 (2012): 110-23.