(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 30 November 2016.)

Why Donald Trump? Why, for that matter, Bernie Sanders? Why have two economic populists from outside the American political mainstream set the tone for the recent presidential election? And why did one of them go on to become the President elect, to the shock of many and the surprise of most pollsters? Part of the answer lies in stagnant economic growth (after 1970) and rising income and wealth inequality (after 1980).

These two trends are painstakingly compiled in two recently published books of economic history. Thomas Piketty’s Capitalism in the Twenty First Century (2014) shows that US income and wealth inequality declined starting in 1930, but rose steadily again after 1980. Robert Gordon’s The Rise and Fall of American Growth (2016) shows that US labor productivity was at its peak during 1920-70, but fell off significantly during 1970-2014, despite the information technology revolution.

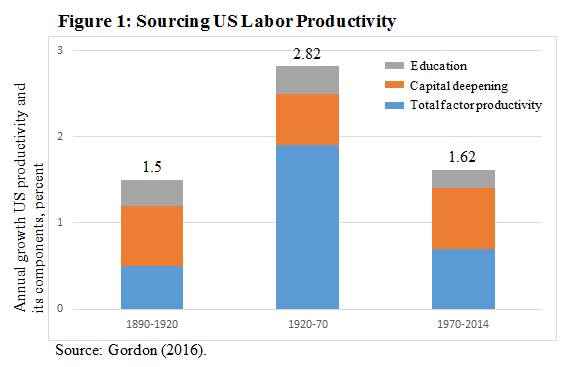

The fast growth of labor productivity from 1920 to 1970, at 2.82 percent per annum (see Figure 1) compared with periods before (of 1.50 percent per annum) and after (of 1.62 percent per annum), is due mainly to total factor productivity, which represents innovation and technical change. Capital deepening is the contribution to labor productivity growth of more capital per worker hour.

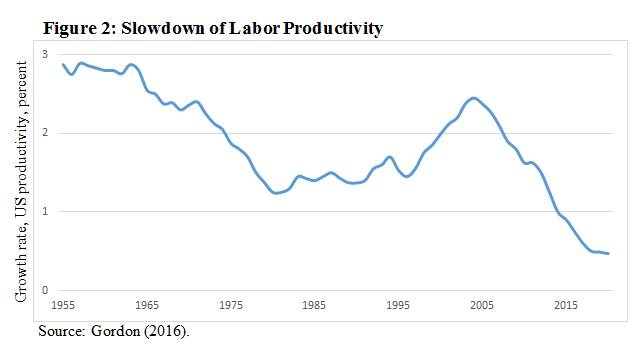

A closer look shows that recent years have been particularly slow. Labor productivity growth was rapid in the 1950s and 1960s at more than 2 per cent, slowed from 1970 to 1994, then sped up again to above 2 per cent until 2004 on the momentum from information technology, in particular computers combined with the Internet, which improved how we work (see Figure 2). But the IT revolution was short lived. From 2004 to 2014, labor productivity fell back to 0.5 percent.

Robert Gordon tells us economic progress occurs much more rapidly in some eras than in others. There was virtually no economic growth for millennia until 1770, only slow growth in the transition century before 1870, and remarkably rapid growth in the special century of the second industrial revolution from 1870 to 1970. That was a century notable for its radical improvement in working conditions on the job and at home. It was a period of unprecedented economic growth and improvements in the health and standards of living for many Americans.

The economic revolution of 1870 to 1970 was unique in human history, unrepeatable because the inventions could happen only once. The master innovations of this period were electricity and the internal combustion engine. These two and a few others made possible the networks to which homes became connected during these decades, networks that gave them reliable supplies of electricity, clean water, access to safe sewage systems, gas for heating and cooking, and, somewhat later, telephone service. Modern conveniences allowed most people in the US to abandon hard physical labor for good and many Americans left their farms and moved to increasingly comfortable cities and suburbs.

The inventions of the special century also made possible radical improvements in the quantity and quality of the food Americans consumed and in the comfort of the houses in which they passed the time not spent at work. Work, too, became far less physically taxing and dangerous. A revolution in transportation took place with the introduction of the automobile.

The period included, as well, the transformation of popular entertainment through the appearance of motion pictures, radio, and television. In the special century, public health and life expectancy took giant steps forward, with a steep reduction in the rate of infant mortality (the availability of clean water had a great deal to do with this) and the virtual elimination of deadly plagues of infectious diseases. A newborn infant could expect to live not to age 45, but to age 72.

Gordon recounts all these changes in detail, and the story he tells is a remarkable one. All the changes he documented have a claim to being the most sweeping and beneficial development in all of human history.

Growth has been slower since 1970 because the advances have tended to be channeled into a narrow sphere of human activity involving entertainment, communication, and the collection and processing of information. This narrow focus explains why the third industrial revolution has been dazzling and disappointing at the same time. Most of the economy only realized a one-time benefit from the Internet and Web revolution, but methods of production in other sectors have changed little since.

According to Gordon, most new technologies of the third industrial revolution –– comprising the digital inventions since 1960, including the mainframe and personal computer, the Internet, and mobile telephones –– have generated only marginal improvements in well being rather than fundamental changes. That shift from significant transformations to minor advances is reflected in today’s lower growth rates of productivity. And there, Gordon concludes, the U.S. is likely to remain for the near future.

Gordon further argues that any consideration of future U.S. economic progress must look beyond the pace of innovation to include the headwinds that retard growth: the rise in inequality, the shortcomings of primary and secondary education, the aging of the country’s population, and its growing government debt.

Recent research found that the share of total employment accounted for by firms no older than five years has declined by almost half, from 19.2 percent in 1982 to 10.7 percent in 2011. The process of creative destruction, by which start-up and young firms become the source of productivity gains by introducing best-practice technologies and methods and shifting resources away from old low-productivity firms, has obviously slowed down.

The slump in net business investments is also reducing productivity growth. But, a reverse causation may also be operating here as a result of the diminished impact of innovations. Firms have plenty of cash that could be invested but they prefer instead to buy back shares, presumably because they cannot find worthy investments when productivity growth is lethargic.

Such lackluster productivity growth precludes the kind of rapid economic expansion and improvements in the standard of living that Gordon describes happening during 1920-70. No wonder so many Americans are upset. They sense they will never be as financially secure as their parents or grandparents –– and, even more troubling to some, that their children will also struggle to get ahead. Anger over the economy is certainly manifesting itself in the 2016 U.S. presidential election.

The real median wage earned by men in the United States is lower today than it was in 1969. Median household income, adjusted for inflation, is lower now than it was in 1999 and has barely risen. These adverse economic trends, piled on top of one another, and contrasting sharply with the expectations that had built up historically in Gordon’s special century, have created a pool of potential recruits to the populist cause.

Stagnation and inequality have created the political discontent that Donald Trump and Bernie Sanders, the two insurgent populists, have tapped in their presidential campaigns. The discontent that Trump and Sanders drew on for their support will remain a force in American public life for many years to come.

Today’s economic morass cannot be blamed entirely on poor productivity growth, or even on inequality. Still, the lack of technological progress is a serious problem. In the medium to long term, even small changes in growth rates have significant consequences for living standards. An economy that grows at one percent doubles its average income approximately every 70 years, whereas an economy that grows at three percent doubles its average income about every 23 years –– which, over time, makes a big difference in people’s lives.

If robust economic progress in the first half of the 20th century helped create a national mood of optimism and faith in progress, then decades of much slower productivity growth have helped create an era of malaise and frustration.

Gordon’s pessimism about the American technological future can be, and has been, contested on two grounds.

He ignores the potential impact of recent breakthroughs in gene editing, nanotechnology, neurotechnology, treatments for mental illnesses, strong and nonaddictive effective painkillers, the use of modified smartphones for medical monitoring and diagnosis, artificial intelligence and smart software that could eliminate many of the most boring repetitive jobs, and other areas.

Although Gordon focuses on the demographic challenges the United States faces, he never considers that today, thanks to greater political and economic freedom all over the world, more individual geniuses have the potential to contribute to global innovation than ever before, for example, from China. There are also more people working in science than ever before, more science than ever before. So there are ample reasons to be hopeful about the future. Innovation is not over in the U.S. or in the rest of the world.

Gordon is not the first economist to be unimpressed by today’s digital technologies. George Mason economist Tyler Cowen was one of the first to warn that apps and social media were having limited economic impact. But, Cowen argues more modestly that the technological future is simply unknowable: There is no firm empirical basis for ether optimism or pessimism.

The biggest reservation with Gordon’s book is his belief that he can forecast future economic and productivity growth rates. Many past advances came as complete surprises. Although the advents of automobiles, spaceships, and robots were widely anticipated, few foretold the arrival of x-rays, radio, lasers, superconductors, nuclear energy, quantum mechanics, or transistors.

Given that economic growth and technological progress are uneven, there may well be bumps on the road when it comes to using computers to significantly improve human well being. But his book, though, does serves as a powerful reminder that the U.S. economy really has gone through a protracted slowdown with profound political consequences; and that this decline has been caused by the stagnation in technological progress.

References

Tyler Cowen, The Great Stagnation, Dutton, 2011.

Robert J Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War, Princeton University Press, 2016.

Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Belknap Press, 2014.