(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 18 January 2017.)

The rising political polarization in Hong Kong and rich nations in recent times can be traced ultimately to the rising economic inequality over the past three to four decades. Political polarization may manifest in different ways — Brexit and Trump are the most prominent examples – but it has its roots in economic inequality.

Tackling economic inequality is never easy and takes time. Very often there are delays in recognizing the problem, delays in devising the appropriate solution, and delays in mustering the political will to overcome the obstacles to the cure.

In this article I consider (1) what are the sources of economic inequality, (2) how they can be tackled, (3) what is the time horizon required for making an impact on the various sources of inequality, and (4) the politically acceptable time scale before polarization becomes intolerable. My focus is on identifying the goals for addressing economic inequality in the next five years.

Political conflict that arises from economic inequality in rich capitalist societies relates primarily to income inequality among households. Income is the annual return from ownership of economically productive assets called capital. Households with a lot of capital will earn a lot of income. In society, the greater the inequality in the ownership of capital, the greater the resulting inequality in incomes.

Capital is usually divided into three simple forms: property capital, human capital, and physical capital. Historically these were known as land, labor and capital. Today, many households may often own a mix of these three forms of capital.

Distribution of Human Capital

Most people are not born with large endowments of any form of capital, and have to accumulate them over time. Human capital is accumulated through learning, which requires investment of one’s own time and moneyed resources.

If one’s parents are poor, it will be difficult to borrow moneyed resources to finance human capital investments. Children in broken families face more difficulties because most are poor and their home does not have a friendly learning environment. Borrowing money through the market for making human capital investments is particularly difficult in free societies because the law prohibits people from indenturing themselves to borrow money. Without other forms of tangible collateral, banks are unwilling to lend to young persons whose creditworthiness is difficult to assess. This is a source of considerable inequality in human capital that produces inequality in earnings (income from labor).

One of the reasons why government often subsidizes education and health care is to equalize access to financing for various kinds of human capital investments. Voluntary charities also help. These are attempts to correct imperfections in the capital market for human capital investments.

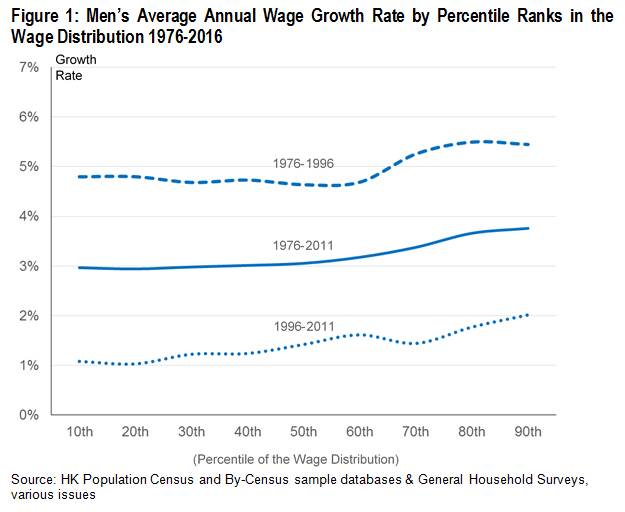

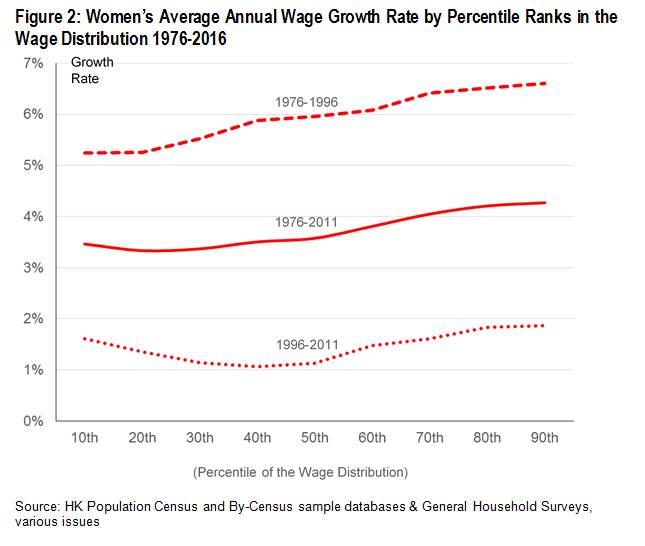

The distribution of human capital in Hong Kong can be best studied by examining the distribution of wages, which is the measure of its return. Between 1976 and 2016, the average annual wage growth rates for men increased by 3.0-3.7% and for women 3.5-4.2%. Figures 1 and 2 below plot these growth rates of men and women against the percentile ranks in their respective wage distributions. Three results stand out.

First, growth in the average annual wage rate was higher among higher-income earners for both men and women. This means that wage distributions have become more unequal over time.

Those at the bottom ends of the distribution saw annual wage growth of 3.0% for men and 3.5% for women, while at the top ends the annual wage growth was 3.7% for men and 4.2% for women. More significantly, wage growth among the middle class was closer to the lower wage class than the upper wage class.

When the middle class gradually converges on the lower class over long periods of time, we have a serious problem of growing near-poverty. Politically this is a far more serious problem than rising poverty among the lower wage class because there are far more people in the middle class than the lower class; and the middle class is usually better educated and politically more active.

Second, the increasing inequality of wage distribution among both men and women implies that household earnings are also likely to become even more unequal over time. This is driven by the widely observed tendency of positive marital sorting, where high wage men marry high wage women, and low wage men marry low wage women. This phenomenon is particularly acute in Hong Kong because of the opportunity for low wage men to find low wage wives across the border.

Third, the average annual wage growth during 1976-96 was much higher than in 1996-2016 (see also Figures 1 and 2). In the first period it grew at a rate of 4.7-5.5% for men and 5.2-6.6% for women. In the second period it grew at a rate of 1.0-2.0% for men and 1.1-1.8% for women.

One reason for the slower wage growth in the second period was the overall slowdown of the world economy. Another reason was that the main benefits of China’s opening were reaped in the first two decades, when Hong Kong experienced a structural transformation from a manufacturing to a service economy.

The productivity of the labor force was also diluted by the substantial influx of new immigrants, mainly women from the Mainland, into the labor force. From 1976 to 1996, 339,500 men and 354,300 women arrived as residents, but from 1996-2011, 183,800 men and 388,400 women had arrived as residents.

Many of these women were unskilled and their entry to the workforce had an impact on wage growth that meant women’s wage growth stopped outpacing that of men’s in the second two decades. Meanwhile, the supply of men available to join the work force ceased to grow completely. Male employment numbers have stagnated at 1.9 million since 1996 while those of women have risen from 1.1 million in 1996 to 1.6 million in 2016.

The migration of manufacturing jobs across the border during 1976-1996 raised the wages of the current generation of less skilled workers, but deprived the next generation of less skilled workers from accumulating new manufacturing skills. Wage inequality was further worsened by the large influx of mostly female unskilled immigrants. This has also created more political pressure for minimum wage increases and work-hours legislation.

The rising inequality in wages is therefore primarily a result of the worsening skills distribution of the population. It is also why Singapore’s productivity has been able to catch up with Hong Kong’s in the past two decades. Higher education places here have also ceased expanding since the mid-1990s, which would help to address the skills imbalance.

Looking ahead, the pressure on government to invest in innovation and technology infrastructure to create higher value-added jobs will only succeed if we can train and attract a highly skilled labor force and new entrepreneurs start new businesses.

Such training has to start in early childhood and be sustained through secondary and university schooling. And simply throwing money at training will not automatically lead to human skills accumulation. Families also play an important role in investing in children both before and during their schooling.

Intervention policies have to be smart. Government supported childcare centers, while politically popular, will worsen skills accumulation among children by substituting a motivated parent with a paid service provider.

In the US, productivity, while still leading the world, has been slowing down since the 1970s largely because of a lack of investment in education and the breakdown of the family. Hong Kong has experienced a similar trend since the mid-1990s. The slowdown of education investment results in too few workers with high-end skills and too many with low-end skills, leading to wider wage disparity between highly skilled and less skilled workers.

Technological progress has worsened the situation because of the increasing bias towards the employment of skilled workers.

Investing in education and early childhood care is critical for alleviating wage inequality in the long run, but it will not yield many dividends in the short run. Since short-term results count more in an open society — politicians have very high discount rates –– do not expect education and training policies to be high on the political agenda in the coming Chief Executive elections.

The polarized political atmosphere of Hong Kong, combined with the stronghold the opposition politicians have over the education vote and the pro-establishment politicians have over the labor vote, means it would be unwise for government to be too active in this area.

This is unfortunate, but such are the compelling realities of politics in Hong Kong. Tackling wage inequality in the next five years will not yield reliable popular support for politicians.

Distribution of Physical Capital

Attention therefore turns to other forms of capital. Starting a business is the usual way of accumulating physical capital. In today’s economy, stock markets allow people to invest in companies without having to start their own business. The development of financial capital has allowed the ownership of physical capital to be distributed across a wider population.

Starting a business and investing in companies requires knowledge and skills that have to be built up over time. It also needs financing, which requires either accumulating savings or building up one’s creditworthiness to be able to borrow in the market. Unless one inherits a business, it will take time to accumulate physical capital (or financial capital) and the distribution of physical and financial capital is usually quite unequal.

Economic policies to redistribute physical and financial capital, or incomes derived from them are highly detrimental for economic growth and should be avoided at all cost. Their effect on economic inequality is also unknown. Hong Kong’s low and simple tax regime has been one of the two most fundamental policy pillars underpinning growth, and it is not advisable to tamper with it.

Since only a third of economically active individuals pay taxes, there is little popular support for complicating the existing tax regime and raising tax rates. The government would be foolish to tinkle with this in the next five years.

Distribution of Residential Property Wealth

Rising residential property values and rents in major urban centers have become an important source of economic inequality among populations in rich countries. This has made property the best store of value.

In Hong Kong, the ownership of residential property is a major determinant of a family’s wealth position and a more important contributor to economic inequality than either human capital or physical and financial capital. Those with property are able to share in the gains of rising property values while those without means fall behind.

Property prices are high and rising in Hong Kong because demand has continued to outstrip supply, especially at the low end of the wage distribution where it has been fuelling demand for sub-divided housing. Historically, the postwar influx of immigrants was the primary driver of housing demand growth. But what constitutes a household is an evolving concept.

With growing economic prosperity, many young adults no longer wish to live with their parents, even when their parents have reached old age and passed retirement. The rising number of divorces also leads to new household formation that mostly occurs at the low end of the wage distribution. Meeting housing demand in Hong Kong is not merely about shelter provision but satisfying the aspiration for homeownership.

That aspiration is not deterred by rising property prices, but it has become frustrated by its increasing unaffordability. The barrier to affordability is often viewed as the inability of earnings to catch up with rising property prices. This is not incorrect, but it is not the most important reason.

The real difficulty is in arranging financing for making home purchases. Banking regulators demand an exorbitant down payment on mortgage loans in order to ensure that banks remain safe. The “have-nots” are disadvantaged because they have no other means of borrowing.

Economic inequality in homeownership is greatly worsened when housing capital markets become seriously imperfect and are unable to help middle income households finance their home purchases.

The inability to finance property ownership also effectively locks out most of the young generation from sharing in the fruits of future economic prosperity. Some property-owning parents are willing to help finance their children’s home purchases, but for those without property-owning parents, there is little hope. Without a functioning mortgages loan market, economic inequality passes onto the next generation and is multiplied.

Many observers have recognized that the “housing ladder” is no longer functioning. Low-income households residing in public rental housing units cannot move into Homeownership Scheme units when they become lower middle-income households, or later move into private residential units when they become middle-income households. This break in the “housing ladder” is in effect a capital market failure created by regulatory demand for exorbitant down payments.

The current policy of building ever more public sector housing units will not meet the aspiration for homeownership among most existing public renter households. Without a housing ladder, the large number of low-income public rental households cannot hope to improve their economic lot in life. Furthermore, the present housing construction policy even fails to meet the growing new demand for housing units each year.

It is important to recognize that the unequal distribution of housing wealth originates not only from high property prices due to a shortfall of housing supply, but also capital market imperfections created by the high down payments required by the regulator. Addressing this issue will go a long way to alleviating economic inequality in Hong Kong and make a difference to political polarization.

Irreversible Reforms with Impact

This is a readily achievable goal in the next five years – within one Chief Executive’s term. It entails devising smart policies to unlock the hidden values of public rental housing units and government subsidized for-sale flats. Apart from easing inequality in housing wealth, it would also secure the foundations of private property ownership for guaranteeing equality and freedom in society.

To make this work, the government should produce new public housing units for purchase by eligible households, sell existing public rental units to sitting tenants, and revise the unpaid land premium of Homeownership Scheme units. In addition to bank financing, the government should also provide supportive long-term financing.

Tackling economic inequality in the next five years will be possible if it is targeted at narrowing the gap in housing wealth, rather than narrowing the gaps in human capital or physical and financial capital. Without the resounding success of a new public housing reform strategy, it may not be politically feasible to make other major policy changes under the current divisive political environment. Failing to reform our public housing policies risks further political polarization that may be even more difficult to reverse in another five years.

President Obama’s most important domestic achievement has been the provision of health care insurance benefits for 20 million Americans who previously lacked coverage. This is a modest gain in a country with 320 million people, yet it is now under serious threat of being reversed by the incoming administration. Public housing reform in Hong Kong would benefit nearly half the population. And it would be the kind of change that would be impossible to reverse. Politically divisive economic inequality would forever be eliminated.