(This essay was published in South China Morning Post on 18 January 2017.)

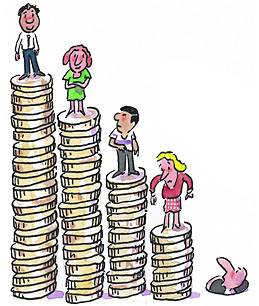

The recent rise in political polarization in Hong Kong and rich nations can be traced ultimately to rising economic inequality over the past three to four decades.

One source of inequality is human capital investment. Those born into poor families cannot hope to get money to finance such investments. Government often subsidizes education and health care to equalize access to this financing and correct imperfections in the capital market.

The distribution of human capital in Hong Kong is evident in the distribution of wages, which measures its return. Between 1976 and 2016, the average annual wage growth rates for men increased by 3.0-3.7% and for women 3.5-4.2%. Three results stand out.

First, the higher growth rates applied to higher-income earners, indicating wage distributions became more unequal over time. Wage growth among the middle class was closer to the lower wage class which, over time, could lead to a serious problem of growing near-poverty (not poverty). There are far more people in near-poverty than poverty; and the nearly poor are politically far more active.

Second, the increasing inequality of wage distribution implies household earnings also likely became more unequal because high wage men tend to marry high wage women, and low wage men to marry low wage women. This phenomenon is particularly acute in Hong Kong because of the opportunity for low wage men to find low wage wives across the border.

Third, wages grew at a much higher annual rate during 1976-96 than 1996-2016. In the first period they grew 4.7-5.5% for men and 5.2-6.6% for women, while in the second period they grew 1.0-2.0% for men and 1.1-1.8% for women.

One reason for this was the overall slowdown of the world economy. Another reason was that the main benefits of China’s opening were reaped in the first two decades, when Hong Kong transitioned from a manufacturing to a service economy.

The productivity of the labor force was also diluted by the substantial influx of new immigrants, mainly unskilled women from the Mainland, into the labor force.

The rising inequality in wages is primarily a result of the worsening skills distribution of the population. But investments in education and early childhood care will take years to yield dividends. So do not expect education and training policies to be high on the agenda in the coming Chief Executive elections.

Faster results in addressing economic inequality could be had, however, by focusing on physical capital or financial capital, in particular residential property wealth.

In Hong Kong, the ownership of residential property is a more important contributor to economic inequality than human or financial capital.

The aspiration to become a homeowner is not deterred by rising property prices, but in large part the real difficulty is in arranging financing for making home purchases.

Banking regulators demand an exorbitant down payment on mortgage loans in order to ensure that banks remain safe. The have-nots are disadvantaged because they have no other means of borrowing, just like children from poor families need public education and health care.

Many observers have recognized that the “housing ladder” no longer functions. Low-income households residing in public rental housing units cannot move into Homeownership Scheme units when they become lower middle-income households, or later move into private residential units when they become middle-income households. The breaking of the “housing ladder” is in in effect a capital market failure created by regulatory demand for exorbitant down payments.

Addressing this issue would go a long way to alleviating economic inequality and make a difference to political polarization.

This is a readily achievable goal in the next five years – within one Chief Executive’s term. It requires smart policies to unlock the hidden values of the public rental housing units and government subsidized for sale flats.

To make this work, the government should produce new public housing units for purchase by eligible households, sell existing public rental units to sitting tenants, and revise the unpaid land premium of Homeownership Scheme units. In addition to bank financing, the government should also provide supportive long-term financing.

Economic inequality can be tackled in the next five years if the target is narrowing the gap in housing wealth. Otherwise, under the current divisive political environment, it may not even be politically feasible to make any progress on other major policy matters. Failing to reform our public housing policies risks further political polarization that may be even more difficult to reverse in another five years.

President Obama’s most important domestic achievement has been to provide health care insurance benefits for 20 million Americans who previously lacked coverage. This is a modest gain in a country with 320 million people, and it is under serious threat of being reversed by the incoming administration. Public housing reform in Hong Kong would benefit nearly half the population – and be the kind of change that would be impossible to reverse. Politically divisive economic inequality would forever be eliminated.