(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 25 January 2017.)

For many years, Oxfam has been pushing for pro-poor policies through its research, advocacy campaigns, public education, and support for local organizations’ poverty programs. In Hong Kong, it has made good progress, evident in the establishment of the official poverty line, the enforcement of the minimum wage and a Low-income Working Family Allowance, all of which were advocated by Oxfam.

Some of Oxfam’s services are certainly very valuable, but the policy research that informs its advocacy campaigns and education programs is unfortunately wrong-headed. This makes its influence on policy and public understanding quite worrying.

To be fair, Oxfam recognizes that problems relevant to poverty are interconnected with other issues. But still, it proposes a casual minded smorgasbord approach to tackling poverty by turning each factor that is connected to (or correlated with) poverty into a policy goal, with very little consideration of the underlying causal relationships behind the correlations.

For example, it advocated successfully for the adoption of an official poverty line in Hong Kong drawn at half the median household income according to household size. Those living below that are considered poor. But is this a good way to identify poverty? And is the percentage of households below the poverty line a sensible measure of rising or falling poverty in the population?

Oxfam is also behind the Low-income Working Family Allowance proposal, believing that such a policy measure can indeed help households in poverty as measured by the official poverty line.

It has also advocated raising minimum wages to help the poor on the presumption that individuals with low wages have to be poor. But do minimum wage individuals come only from households that are poor? If not, then why would a minimum wage help alleviate poverty?

These are not the only local poverty issues that Oxfam supports. There are many others, but the above three have been implemented so their effects can be evaluated.

On minimum wage, for instance, we can see in data from the General Household Survey figures for 2011.Q3-2012.Q2 (the period immediately following the implementation of the minimum wage law) that 36.4% of minimum wage workers came from households with incomes above the median level.

In addition, 80.5% of the minimum wage workers were from households with incomes above the 20th percentile level, which is roughly what the official poverty line defines as those households that are not considered poor. This means the minimum wage law pretty much picks out poor households randomly. Furthermore, 5.8% of minimum wage workers were from households with incomes above the 80th percentile level.

The analytical error here is the false presumption that low wage individuals must come from low-income households. This is obviously not the case – in Hong Kong or elsewhere. It has also been seen in the US, the UK, Canada, and many other countries where empirical research has been undertaken.

Why doesn’t Oxfam examine such evidence before mounting its advocacy campaigns? I can understand why politicians eager to get elected or reelected into office have decided to support minimum wage increases, but why should Oxfam, an organization dedicated to helping the poor, support policies that obviously cannot succeed? The term “post truth” has become popular lately, but I fear it describes a practice that has a much longer history and its practitioners have for too long gotten away with it.

Oxfam was very active in pushing the government to adopt the official poverty line. But a poverty line defined as half the median wage guarantees that poverty will never be alleviated, much less eliminated. This is in sharp contrast to the achievements of the UN and World Bank, which set Millennium goals to cut the world’s poor population living below US$1 per day, later revised to $1.90 per day.

At its peak in 1970, 2.2 billion (or 60.1%) out of the world’s 3.7 billion people lived on less than $2.00 per day. Even in 1981, 44.0% or the world’s population was living below the poverty line (redefined as US$1.90 per day); this figure will fall to 9.6% in 2015. What these figures have in common is they adopt a cost of living adjusted absolute level of income in defining poverty, and not a relative level that increases as standards of living rise due to increasing productivity.

This is certainly a more sensible definition of poverty than one based on relative income levels. The latter would be more appropriate if one were searching for a measure of inequality, but not poverty. Our Comprehensive Social Security Assistance (CSSA) scheme uses a qualifying level of income that adjusts for a constant cost of living and not a moving standard of living. Its underlying conception of poverty is based primarily on absolute income levels.

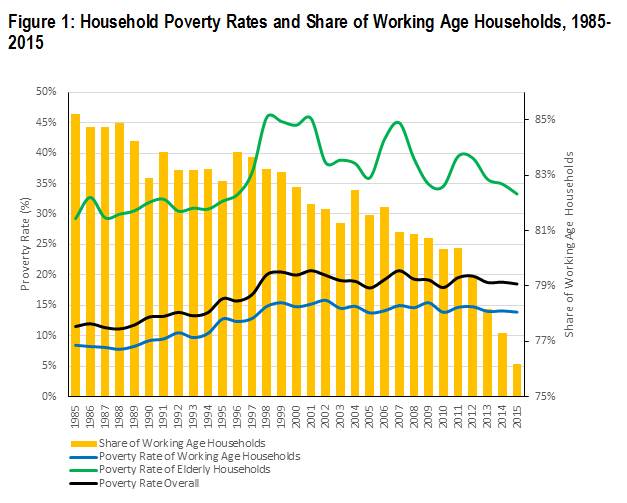

To see the absurdity of such a definition, let us examine household and individual poverty rates from 1985 until 2015.

According to the various issues of the Hong Kong Poverty Situation Report, the number of households below the poverty line increased from 541,000 in 2009 to 570,000 in 2015, but the number of poor people living in such households decreased slightly from 1.348 million in 2009 to 1.345 million in 2015. These figures do not factor in government-provided poverty alleviation measures.

So the number of individuals who were in households below the official poverty line was quite stable in a period when population numbers were still rising. The number of households was increasing more rapidly, reflecting the growth of small households as young adults did not want to live with their parents and there was new family formation due to marriages and remarriages.

Using data from the General Household Survey, we can apply the official poverty line all the way back to 1985. The household poverty rates include government recurrent cash transfers and can be estimated separately for working age households (age 20-64) and elderly households (above the age of 65) , and for economically active and inactive households. We find some rather fascinating results.

The single most important result is that the household poverty rates are remarkably stable over time when we examine them separately among working age households and elderly households. They vary from 8.5% in 1985 to 13.9% in 2015 for working age households and from 29.3% to 33.3% for elderly households (see Figure 1). The number of persons living in working age households below the poverty line increased from 370,000 to 790,000 and from 111,000 to 394,000 among elderly housheolds. The overall household poverty rate have risen over this period mainly because of the rising share of elderly households.

Measured poverty rates are necessarily higher because most of them are not working and have no income or very low incomes. An official poverty line defined on income that is applied to elderly households makes very little sense and cannot reveal whether they are poor or not. At best, an official poverty line should only be applied to working age households.

Poverty rates among economically active working age households have been remarkably stable – averaging around 10.0% over the three decades from 1985-2015. In the first decade the rate was at its lowest at 8.1%, then 11.6% in the second decade, and 10.7% in the third decade.

The poverty rate in the first decade was probably unusually low and can be attributed to the early period of China’s opening when productivity in Hong Kong increased rapidly, benefitting many less-skilled workers. Since the Asian Financial Crisis, the poverty rate has risen on average by over 2.0% but it has since remained quite stable.

The overall working age household poverty rate was also quite stable over the period 1985-2015 because it was dominated by economically active households, which constitute on average 94.6% of all working-age households. Not surprisingly, among economically inactive households, the poverty rates are higher, averaging 57.2%.

It is worth looking more closely at the labor force to understand the sources of poverty in Hong Kong. Since 1996, the male labor force has been stagnant at 1.9 million and the female labor force has grown from 1.1 million to 1.6 million (excluding domestic helpers). Productivity has not grown as both the quantity and quality of the labor force has not improved by very much. An increasingly tight job market has attracted many less-skilled women workers, mostly recent immigrants, into the labor market but this does not help reduce the share of low-income households below the poverty line.

In addition, among working age households, a growing share of low-income households below the poverty line has been divorced households, rising from 1.7% in 1985 to 9.1% in 2015, while the share of married households below the poverty line has declined from 78.2% in 1985 to 67.7% in 2015.

The growing feminization of the labor force at the low income end of the wage distribution and the rising incidence of divorced households have been the two most important sources of poverty in Hong Kong. Poverty alleviation therefore should focus on the changing patterns of household formation and breakdown.

Another area of poverty alleviation where Oxfam has been prominent is in advocating for the Low-income Working Family Allowance (LIFA), which was launched last year. This is refined variation of economist Milton Friedman’s original proposal to introduce a negative income tax to help low-income households by providing them with direct cash awards.

An estimated 360,000 households (after deducting cash subsidies) and 270,000 households (if both cash and in-kind benefits are deducted) were below the official poverty line in 2015. A reasonable expectation was that about 200,000 economically active households would benefit from the LIFA Scheme. Eventually, only around 31,800 households applied for the Schemeof which 20,633 were approved. It turned out that in applying the official poverty line, only about one-tenth of the estimated number qualified.

Why had the estimates so grossly missed the mark?

All programs have teething difficulties, but it is unlikely that any reasonable adjustments will bring the number of qualified households anywhere close to 200,000 households. Oxfam, which is a strong advocate of the LIFA Scheme, had estimated in its own research in 2014 that there were 189,500 households. It now surmises in their Hong Kong Poverty Report 2011-15 that: “The low application rate is likely due to the harsh criteria, complicated application procedures, and the lack of language support to ethnic minority families.” But ten times is far too large a gap to blame on teething difficulties.

The calculations were based on the quarterly General Household Surveys. Is it possible that the incomes in these surveys could have been grossly underreported?

After all there is difference between causal surveys and stating the amount of income one earns under oath when applying for the LIFA. Perhaps there is some amount of underreporting, but on such a large scale and by such a wide margin seems incredible.

Our direct experience of poor households is that they tend to stay poor for fairly long periods of time. Using Milton Friedman’s concept of permanent income, one can describe a poor household to be one whose income tends to be low for many years, perhaps even decades. But in any particular year, a household’s income may have a large component of transitory income that fluctuates considerably over time. Such a situation is particularly true for low-income households, where job security is low, or work is casual and part-time in nature.

The problem with the poverty line approach is that when one works with household income distribution data in any particular year, it is easy to fall into the trap of thinking the household’s position, as defined by its income in the distribution at any moment in time, will remain relatively stable over time. This may not be the case at all among low-income households. The population’s poverty rate may remain stable over time, but those living below the poverty line may change from year to year.

A household’s income in any year is a snapshot of a moving number. If that income moves up or down, then the household will appear in some photo shots but not in others. In Chasing the American Dream, sociologists Mark Rank, Thomas Hirschl, and Kirk Foster looked at 44 years of longitudinal data for individuals aged 25 to 60 to see what percentage of the American population experienced either poverty or affluence during their lifetimes. The results were striking.

It turned out that 12% of the population found themselves in the top 1% of the income distribution for at least one year. What’s more, 39% of Americans spent a year in the top 5% of the income distribution, 56% found themselves in the top 10%, and a whopping 73% spent a year in the top 20% of the income distribution. So, a majority of Americans experienced at least one year of affluence at some point during their working lives. This is just as true at the bottom of the income distribution scale, where the shares of Americans experiencing poverty or near-poverty at least once between the ages of 25 and 60 were 40% and 54%, respectively.

Since poverty is defined on a single premise, one is led to think of poor households as staying poor for some time. But one cannot help thinking that there is something wrong with the conception of poverty that is being suggested by the poverty line.

If income in any particular year is transitory, it is highly likely that many households near but below the official poverty line may have little interest in applying for LIFA if it is the result of a transitory downward fluctuation. Only those households that expect their incomes to be consistently below the expected poverty lines in the near future will be motivated to apply.

Current application rates suggest that the share of such households that can be considered as truly in poverty are quite low among the estimated 200,000 economically active households below the poverty line. But then there may be many more households that are in near poverty, and these would include even those whose income in a particular year is above the poverty line.

I believe it is better to say such households are in near poverty. And they may well make up one-third of the population. They are the ones that lack employable skills in high-skilled jobs, and who are unable to afford the exorbitant downpayment to puchase a mini-sized home. Households in near poverty are far more numerous than those in true poverty. Their plight needs to be better addressed in the next five years. Housing ownership will play a big part in the immediate solution and in the longer term income will depend on skills investment.

Defining poverty by income alone has many limitations, especially monthly income in any one year. Poverty is a multidimensional problem and is not amenable to quick fixes. Oxfam does fabulous work in helping the poor and disadvantaged in many countries, and in Hong Kong. Wandering into policy is not its forte.