(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 1 November 2017.)

Hong Kong has a current labor force (not including foreign domestic helpers) of 3.64 million that is projected to peak in four years at 3.68 million. Thereafter, the labor force will continue to decline uninterrupted at an average annual rate of 0.36% to 3.13 million by 2066. If this forecast comes true, surely the future of Hong Kong as an economic powerhouse has a very weak hand.

Declining fertility rates have driven us into this dire state. But more importantly, a fortress mentality towards the admission of foreign workers and immigrants has made it impossible to mitigate the effects of low fertility rates.

Consider Singapore’s contrasting experience. Its labor force increased at an average annual rate of 2.4% between 1986 and 2016, By comparison Hong Kong’s grew at a mere 1.0%.

Singapore’s total labor force in 2016 was 3.57 million, of which 1.40 million (or 45.6%) were non-residents. Foreign domestic helpers (the most important source of foreign workers) working in Hong Kong are only 8.60% of the total labor force. The quality of Singapore’s resident population as measured by average years of schooling has also overtaken Hong Kong, after being lower than Hong Kong’s up to 2001.

In today’s knowledge economy, I find this a compelling explanation for why Singapore’s GDP per capita was US$53,000 in 2016, a significant 21 per cent higher than Hong Kong’s US$44,000.

Sustaining economic growth does not necessarily require a city to grow its own population. What matters vitally is its ability to attract talents from outside the city’s boundaries to come and enrich its labor talent pool. London and New York City could not have become the global economic centers they are today if their cities were powered only by the offspring of their original inhabitants.

New York and London owe their stellar position to their ability to attract the best in the world to live and work there. And their cities have grown far beyond their boundaries into the surrounding areas to become great metropolitan areas. The ability to sustain the circulation of talent through these metropolitan areas is vital to sustaining their economic dynamism.

Tackling Labor Shortage

Hong Kong’s labor shortage has two main features. Knowing what these are is important if we want to identify effective policy measures for making the best of a challenging problem.

First, most of the population decline in the next 25 years will be among the younger labor force (age below 45), whose numbers are predicted to fall from 1.97 million in 2016 to 1.49 million in 2041. The older labor force (age above 44) will rise from 1.65 million in 2016 to 1.73 million in 2041.

Second, most of the decline in the next 25 years will be in the male labor force, falling from 1.99 million in 2016 to 1.80 million in 2041. The female labor force will rise moderately from 1.63 in 2016 to 1.67 million in 2041.

The slow growth of the younger labor force is of particular concern because it means the problem can only be corrected by attracting foreign workers and immigrants. This will be very difficult given our fortress mentality, our heightened localist political sentiments, and highly divisive politics.

The government has been targeting the descendants of Hong Kong emigrants. This is politically wise, but it is not clear how effective it will be. Obviously recognition of overseas professional qualifications will be necessary if returnees hope to find a fulfilling job here. A choice education curriculum for their children and quality health care that meets their demands must also be available.

Supplying affordable housing will be necessary and this requires a major reorientation of our housing policies towards homeownership. To overcome local political resistance, it will be necessary to reorient local public housing policy towards privatization and homeownership so that existing and future occupants in these housing estates can benefit from the rising prosperity created by a more open population and immigration policy. The fortress mentality has to be tackled head on and cannot be shied away from.

The importance of addressing the younger labor force shortage cannot be underestimated because they are the most creative and dynamic element of the labor force. Most individuals start their businesses relatively young and become employers after gaining 10 years of work experience.

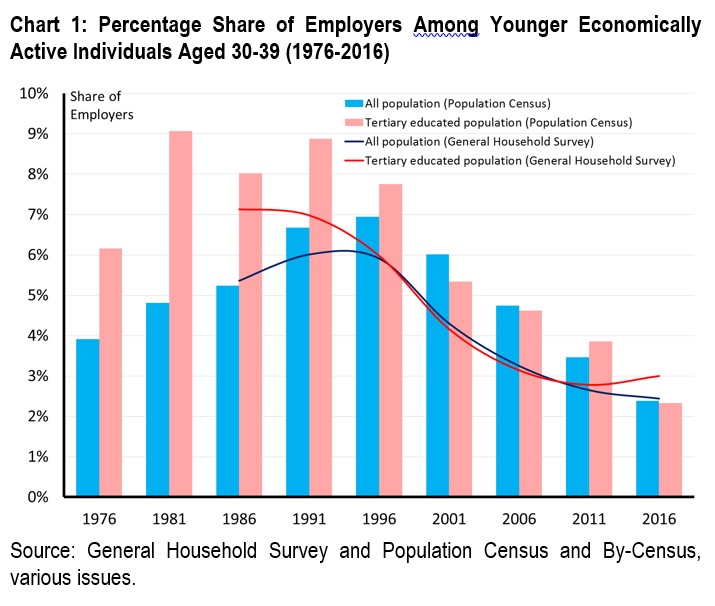

Chart 1 confirms that the percentage of employers among economically active 30-39 year olds has been declining since the mid-1990s, from about 7-8 per cent to a present low of around only 3 per cent. This implies the number of new entrepreneurs has been falling.

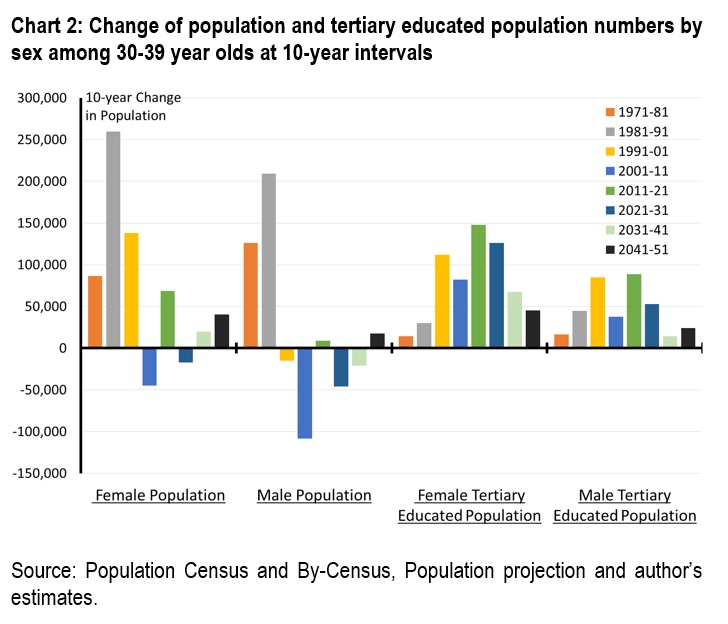

The primary reason for this is Hong Kong’s changing demographic structure. Chart 2 shows the 10-year change in the number of 30-39 year old men and women. For men, the number increased by 125,900 in 1971-81 and 209,300 in 1981-91, then fell by 14,900 in 1991-2001 and 108,300 in 2001-2011. It is projected to seesaw over the near to medium term, up 9,000 in 2011-2021, down 46,100 in 2021-31, down 21,000 in 2031-41 and up 17,700 in 2041-51.

The decline of 30-39 years old women since the mid-1980s is more moderate because of the arrival of recent immigrant women from the Mainland through cross-border marriages and family reunion considerations. The number of women increased by 86,500 in 1971-81, 259,800 in 1981-91 and 137,900 in 1991-2001, and decreased by 44,600 in 2001-2011. It is projected to increase by 68,600 in 2011-2021, fall by 17,300 in 2021-31, and increase by 19,700 in 2031-41 and 40,500 in 2041-51.

If there is no political breakthrough in attracting foreign workers and immigrants, then it will be imperative that we upgrade our labor force quality. For the foreseeable future, the growth of a younger labor force will have to be met by drawing from the female population, whose numbers are growing faster.

Chart 2 also shows that beginning from the decade of 1991-2001, the number of women with tertiary education (both degree and non-degree qualifications) has been increasing at a significantly faster pace than men among 30-39 year olds.

For men, the increase was 85,000 in 1991-2001, 38,000 in 2001-2011, and is projected to be 88,800 in 2011-2021, 52,600 in 2021-31, 14,300 in 2031-41 and 24,900 in 2041-51. For women, the increase was 112,260 in 1991-2001, 82,300 in 2001-2011, and is projected to be 148,000 in 2011-2021, 126,200 in 2021-31, 67,500 in 2031-41 and 45,500 in 2041-51.

Women will make up half the total labor force in future, if not more. More importantly, within the tertiary-educated workforce they will be in the majority. This will require a shift in workplace practice, human resource management practice, childcare support provision for working mothers, education and training to meet the demands of women workers (including English language command), new thoughts of family and work balance issues, and so on.

Hong Kong’s enormous and growing labor shortage in the world’s fastest growing region could turn the city into the first female-dominated workforce in the coming decade. The city could rise to become the world’s shining city on the hill, where men and women forge a new division of labor both at home and in the workplace.

As often in history, major transformations are seldom planned and anticipated, but rather thrust upon us by forces that we are often unaware of and can only dimly comprehend. Life asks that we make it work for everyone going forward. Electing our first female Chief Executive into office this year is therefore a fitting sign of the times.