(This essay was published in the South China Morning Post on 29 August 2018.)

A tenant assigned to a public rental flat can pretty much stay there either until he dies, trades up into a subsidized homeownership flat, or on rare occasions, surrenders the flat because he has become well off. The lack of circulation of public rental flats has many negative consequences, particularly in the wake of escalating property prices.

While attention has focused on the necessary step of increasing housing supply to address the housing shortage, there is a more immediate step that could be taken: lift the restrictive regulatory barrier that currently prevents tenants in public ownership and rental flats from leasing or sub-leasing their flats.

My proposition may appear counter-intuitive – how can we address the housing shortage without increasing housing supply? But if we carefully think through the economics of housing allocation in Hong Kong, there is indeed a huge free lunch that can be had.

Hong Kong’s public housing sector accommodates half the population. Two-thirds of residents in this sector live in public rental flats and one-third in subsidized homeownership flats.

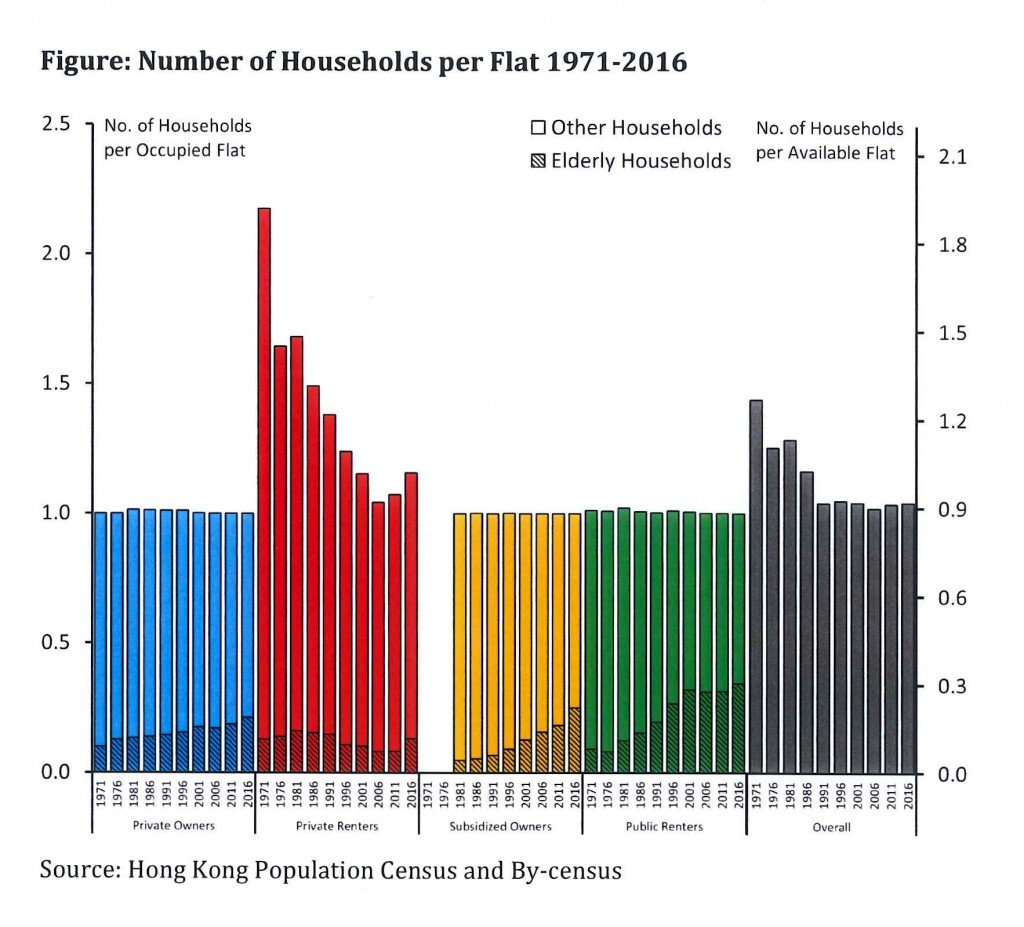

Since the 1990s, the ratio of households to flats available for occupation has been very stable (see Figure). But this stability is deceptive given the rising number of sub-divided private rental housing units and the growing queue of applicants and long waiting times for public rental flats.

Why is there such a huge gap between figures and facts? The answer lies in the degree of sharing per occupied flat. For private owner flats, subsidized public owner flats, and public renter flats, that degree was constant at 1.0 from 1971 to 2016 (see Figure).

Private owners can afford not to share with others, while the other two categories are not allowed to share except with approved and eligible family members.

This situation has left private rental flats to take up the slack of the housing shortage, which today is primarily in the form of sub-divided flats. The degree of sharing in this sector increased to 1.16 in 2016, after falling from 2.18 in 1971 to 1.04 in 2006 – an increase that in fact reflects the misallocation and underutilization of public housing flats, where flat sharing is disallowed.

Yet allowing public housing tenants to lease or sub-lease their flats, while still retaining a claim on it, could free up space and at the very least halt and reverse the sub-division of flats. It could also greatly improve the widespread mismatches of households and flats, for example, by allowing tenants to move closer to work or schools.

Leasing or sub-leasing could apply to groups such as elderly individuals who want to move in with their children and grandchildren, relocate to the Mainland, or migrate overseas. In 2016, elderly households (65 years of age or above) in public housing numbered 356,000 and constituted 34.3 per cent of all public rental households and 25.2 per cent of all subsidized public owner households.

Quite a few of these households may be willing to move out of their public flat to pursue other plans if the Housing Authority allowed them to: (1) collect market rent, and (2) reclaim their flat if their situation changed in future – in other words, if their status as a public tenant did not have to be surrendered.

There are also a reported 520,000 Hong Kong individuals working and residing on the Mainland, many of whom fit the profile of public housing tenants and may also be absentee residents, at least from time to time. Their idle flats could also be put to better use by allowing the flats to be leased or sub-leased.

Interestingly, when the government offered incentives to encourage public rental tenants to retire in Guangdong and Fujian, it had to promise that they could return to live in public flats in future if their plans changed, in order to attract interest. My proposal is just a more general scheme that could apply to as many as 1.1 million households in public flats.

It would be reasonable for public flat tenants who leased out their flats to pay “double rent” to the Housing Authority. Subsidized flat owners would pay “triple rent.” The net gain would help many elderly households to obtain some modest additional income for their retirement livelihood.

My educated guess is that over perhaps five years, 100,000 public flats could be released onto the market. This would help stem the sub-division of private flats and provide incentive for developers to stop supplying mini-flats.

For twenty-five years, I have tried to explain why privatizing public flats and allowing them to be freely traded on the open market would significantly increase GDP per capita and create a more equitable distribution of economic income and wealth. So far, these ideas have not been taken up, but my years of research and contemplation on this issue have convinced me that this is the right course forward. Creating a rental market for public flats falls far short of privatization. But one should not let the pursuit of a perfect solution stand in the way of making progress towards the common good.