(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 29 August 2018.)

A tenant assigned to a public rental flat can pretty much stay there either until he dies, trades up into a subsidized homeownership flat, or on rare occasions, surrenders the flat because he has become well off. In a conversation over coffee with a Housing Authority member in the 1990s, I impressed upon him that the lack of circulation of public rental flats was the source of many negative consequences, which would get worse. He was quite convinced but it made no impact on the policies of the Authority.

Since that time, property prices have escalated. After repeated but unsuccessful government attempts to suppress housing demand to halt property price increases, public focus has recently gravitated towards increasing land supply. This is a step in the right direction but alone will not be adequate to overcome our housing shortage challenge.

First of all, increasing land supply is a medium- to long-term solution. Experience in most developed metropolitan centers shows that land and housing supply is indeed highly inelastic. The reason for this has been identified by some of the most important research in the past two decades: it is restrictive regulatory barriers that prevent land and housing from being responsive enough to rising demand.

Hong Kong needs only to change one of these restrictive regulatory barriers in order to alleviate the housing shortage in the short-run. That measure is to create a rental market for public housing, both ownership and rental flats. A rental market in public flats will bring a significant immediate improvement. Although this would not obviate the need for finding more land and scaling up housing construction, if it is not made soon, then the housing shortage will get even worse before it can get better.

My proposition may appear counter-intuitive to most people. How can we possibly reduce the housing shortage in the short run without somehow increasing housing supply? Demand suppression measures have already failed miserably, so what else can be under the magician’s sleeves? Well if we carefully think through the economics of housing allocation in Hong Kong, there is indeed a huge free lunch that can be had. It is like bundles of thousand dollar bills lying on the street waiting to be picked up.

Hong Kong has a very large public housing sector that accommodates half the population. Two-thirds of residents in this sector are housed in public rental flats and one-third in subsidized homeownership flats. Households living in public housing face policy-induced choices that are different from market-driven choices in the private housing sector.

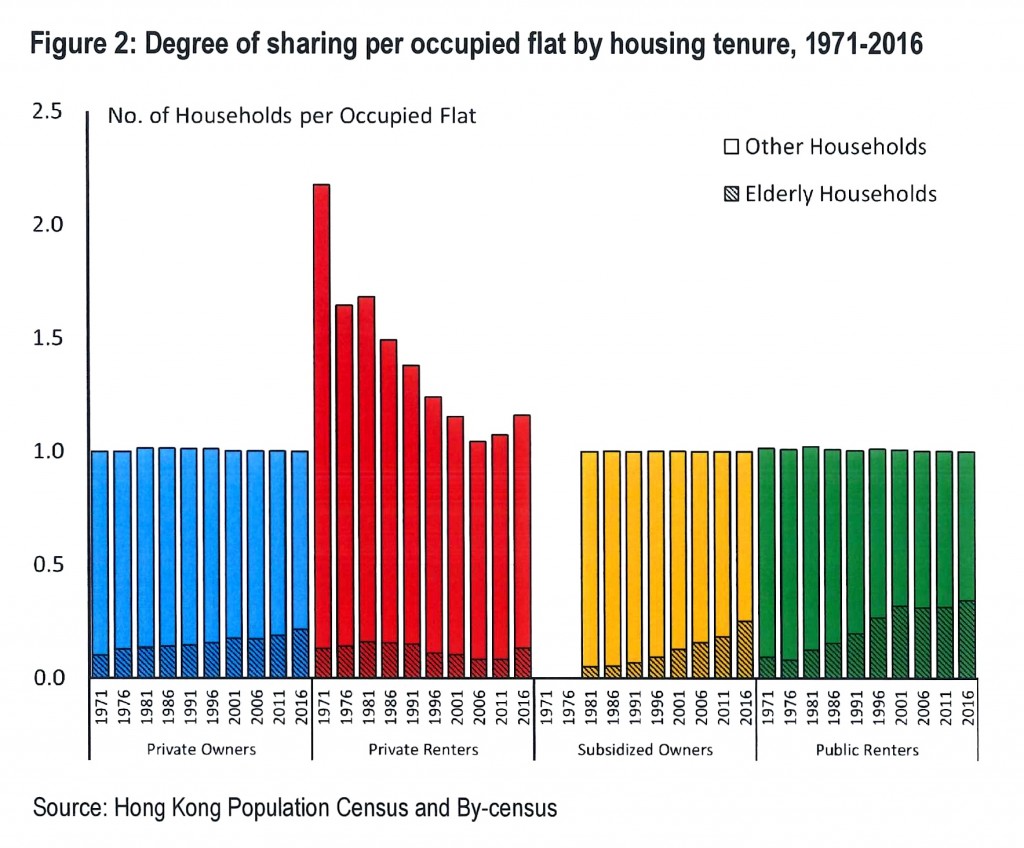

The total number of households divided by the total stock of flats available for occupation in Hong Kong fell from 1.27 in 1971 to 0.92 in 1991 (see Figure 1 below), and has since remained more or less unchanged. Many observers, opinion makers, political leaders, and even some fellow economists mistakenly concluded that the housing shortage ended from the 1990s because there were more flats than households, as reflected by the very stable ratio of households to flats. Even in 2016 the value was still 0.92.

Yet few today would dispute that we have a housing shortage. The rising number of sub-divided private rental housing units and the growing queue of applicants and long waiting times for public rental flats all indicate the housing shortage has become the major social, economic and political problem.

Why is there such a huge gap between figures and facts? Why is our perception of reality so disjointed?

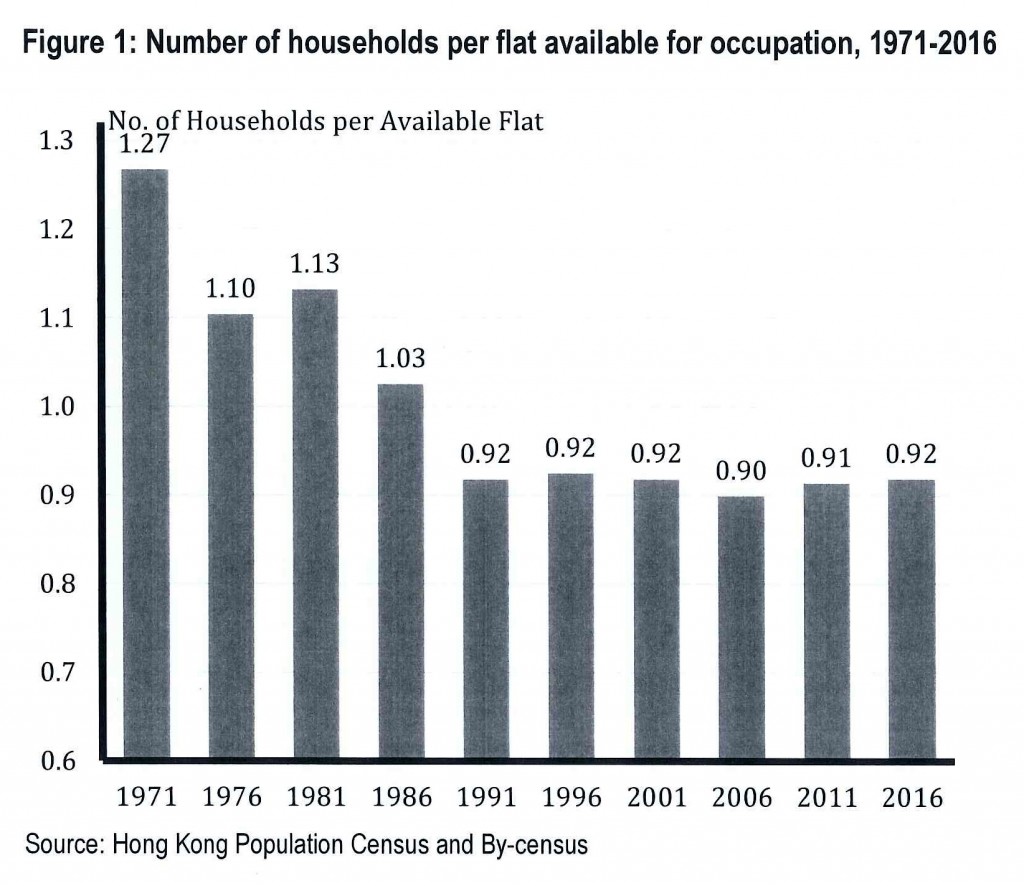

Figure 2 shows the degree of sharing defined as the number of households per occupied flat by housing tenure. The number of occupied flats is necessarily less than the number of flats available for occupation because there are always some vacant flats. The degree of sharing in private owner flats, subsidized public owner flats, and public renter flats was constant at 1.0 from 1971 to 2016. For private owner flats this is not surprising as most could afford not to share their flat with others. But why is sharing totally absent from public housing owner and renter flats?

The reason is it is not permitted. Only approved and eligible family members are allowed to reside in public flats. No sharing is a mandated requirement introduced to prevent residents from leasing or sub-leasing any excess space in subsidized public flats for gain. The residents have no choice in this matter, although some probably do sub-let clandestinely and risk being penalized and even losing their flat if discovered.

Sharing a flat among different households is a phenomenon found almost entirely among private renter flats. Today the sharing comes primarily in the form of sub-divided flats. The degree of sharing fell continuously from 2.18 in 1971 to 1.04 in 2006. But in the last decade the downward trend has reversed and increased to 1.16 in 2016.

The Housing Authority has been the key driver in lowering the degree of sharing by providing affordable public flats to reduce congested living conditions in the private rental sector. One could say that narrowing the gap between the number of flats and households has been the fundamental policy goal of the Authority. It is undoubtedly their proud achievement.

Such a policy was very sensible when there was an extreme gap between the number of flats and households in the post-war period due to the massive immigration of young adult families into Hong Kong. It was a simple summary indicator of what had to be done and what had been accomplished.

The whole approach of counting flats and households to identify a housing shortage is weirdly communist. Households are heterogeneous formations that divide and combine over the life cycle, and respond to incentives and threats. Flats, too, are heterogeneous structures where key characteristics, like owned versus rented tenure and private versus public provision, define critical differences.

To begin with, the number of households is not the same as demand. A family who becomes divorced does not want to live in the same flat. Nor is the young adult living in their parents’ flat, who would rather have a place of his or her own. Households are malleable formations and change alongside society and the economy. While household ageing is no surprise, the rapid and massive increase of cross-border marriages and divorced single parents was not entirely foreseen.

Another crucial point to recognize is that the number of flats should not be equated to supply: it ignores location, quality, size, age, transport links, amenities and everything else that matters to a dwelling. Most relevant for Hong Kong is the attribute that only private flats possess sub-divisibility; public flats do not.

As a consequence, private flats have to absorb the residual unmet growth in housing demand. The smaller the private rental sector, the more exaggerated will be its response. Existing flats have been sub-divided because this is the only sector that is able to respond in this way. In 2016, the share of existing private rented flats was a mere 17.7 per cent of all existing flats, yet they absorbed a significant share of the accumulated unmet growth in demand – public rented flats took up 31.0 per cent, subsidized owner flats 15.6 per cent, and private owner flats 34.0 per cent (with other housing types taking up the rest).

Is the rising degree of sharing in private renter flats an indicator of a housing shortage? Yes, it is. But the degree of sharing also reflects the misallocation and underutilization of public housing flats where flat sharing is disallowed. So a small segment of the housing sector has to bear a big share of the housing shortage burden.

This situation is the result of the fact that public rented and ownership flats cannot be leased or sub-leased. There is no rental market for public flats. Households living in these flats have user rights only and, as I noted in the first paragraph, most spend their entire lives staying in the same flat. Subsidized ownership flats with unpaid “discount” premiums cannot be leased or sub-leased, not even in the restrictive Home Ownership Scheme (HOS) secondary market, which is only a sales and not rental market.

There is little doubt that a rental market for public flats could greatly improve the widespread mismatches of households and flats that have accumulated in the past decades.

Households may wish to change residence for many reasons, such as living closer to work, spouse’s work, children’s schools, parents’ home, a preferred neighborhood, and so on. Creating a rental market in public flats would allow tenants much better opportunities to swap flats. This reduces mismatching of households and flats, but is unlikely to free up more public accommodation space to meet housing demand.

A second type of decision, such as when elderly individuals move in with their children and grandchildren, relocate to the Mainland, or migrate overseas, does have the potential of releasing additional underutilized public flats onto the market without taking up another flat. This would free up more flats and help alleviate the tight housing conditions in the private rental market. At the very least it could halt and reverse the sub-division of flats there.

Who would be interested in the second type of decision?

In 2016, elderly households (65 years of age or above) occupied a total of 261,000 public rental flats and constituted 34.3 per cent of all public rental households. They also occupied a total of 95,000 subsidized public owner flats and constituted 25.2 per cent of all subsidized public owner households. This amounts to a total of 356,000 elderly households living in public flats as either renters or owners, of which 92,000 live alone.

It seems there should be quite a few out of this very large number who would be willing to move out of their public flat to lease it to another party or sub-lease part of the space to meet their preference for living with children and grandchildren, returning to the Mainland, or migrating overseas.

They would be willing to do so if this was permitted by the Housing Authority and they were allowed to: (1) collect market rent, and (2) return to claim their flat if their plans to vacate the unit were to change in future, meaning their status as a public tenant would not be surrendered.

One must understand that there are huge disincentives for a public tenant to surrender his rental flat. He pays a heavily subsidized rent well below market levels. If he moves out, he loses the entitlement permanently. His decision is difficult to reverse. If his future circumstances change, for example, he is not happy living with his children and grandchildren or wishes to relocate back from the Mainland or overseas, then it will be a very long and uncertain wait to get back into a public flat. He would be entirely rational to hold onto the public rental flat and let believe that he is still living there even if he is not.

The subsidized public flat owner has the option of selling his flat. But he will give up 100 per cent of his user rights in exchange for 70 per cent of the “discounted” transfer rights, and this will be an irreversible decision that he may regret if his future circumstances change and he would rather move back to his old flat. So without the right to lease out the subsidized flat, some owners would rather let the flat be idle.

Besides elderly households, there are a reported 520,000 Hong Kong individuals working and residing on the Mainland. While we do not know what proportion of these individuals are also residents of Hong Kong public flats, they are obviously a substantial proportion given their profiles. An estimated two-thirds of them have only primary or secondary level education and half of them stay in employer-provided quarters when they work on the Mainland. It is quite likely that many of them are absentee public flat residents, at least from time to time. Again, could some of these idle flats be put to better use by allowing the flats to be leased or sub-leased?

Interestingly, the government operated a scheme that offered some incentives to encourage public rental tenants to retire in Guangdong and Fujian. It was not seen as very attractive until a promise was made that those who surrendered their flats could return to live in public flats in future if their plans change. What is being proposed now is just a more general scheme that would be applicable to as many as 1.1 million households living in public flats.

Allowing the leasing and sub-leasing of public flats would be a significant policy change. Public flat occupants would be granted new leasing rights, which they do not currently possess. But such policy innovation is not without precedent. The creation of the Homeownership Scheme (HOS) secondary market granted subsidized flat owners the right to trade public flats with eligible buyers without having to repay the initial “discounted” premium.

I think a rental market for public flats will bring enormous beneficial effects in improving the mismatch of flats and households and also releasing a significant quantity of idle or underutilized accommodation space onto the market to provide short-term relief for our housing shortage. I am certain it would be a very actively-traded rental market, unlike the HOS secondary market for property sales.

Public tenants and owners would benefit if they could lease or sub-lease their flats with the certainty that they could get them back in the future. But the benefits would also extend to society in general and many of those now living in poor housing conditions.

I think it would be reasonable for public flat tenants that wish to lease out their flats to pay “double rent” to the Housing Authority. Subsidized flat owners would pay “triple rent.” The net gain would in my view help many elderly households to obtain some modest additional income for their retirement livelihood in Hong Kong or elsewhere.

My educated guess is that over a period of perhaps five years, a hundred thousand public flats could easily be released onto the market. This would help stem the sub-division of private flats and would provide incentive for developers to stop supplying mini-flats.

For twenty-five years, I have tried to explain why privatizing public flats and allowing them to be freely traded on the open market would significantly increase GDP per capita and create a more equitable distribution of economic income and wealth. So far these ideas have not been taken up, but my years of research and contemplation on this issue have convinced me that this is the right course forward. Creating a rental market for public flats falls far short of privatization. But one should not let the pursuit of a perfect solution stand in the way of making some good progress towards the common good.