(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 26 September 2018.)

The Rise of Intangibles

Since the 18th century, when the Industrial Revolution started in England to 1990, business investment centered on the acquisition of real assets, such as machines, tools, computers or office buildings. If a company liquidated, these physical items made up its remaining value. Throughout this period, tangible assets were the only business investments that statisticians counted in their calculations of national economic health.

But since then investment in intangible assets — ideas, designs, research, firm specific human capital, client networks and the like — has been growing. In some developed countries, notably the United States and United Kingdom, commercial investment in intangibles has eclipsed investment in physical assets.

This change has far-reaching significance. The economic properties of intangible assets differ from those of tangible assets. An economy rich in nonphysical assets should behave differently from a “tangible-intensive” economy. Since many statistical metrics don’t take intangibles into account, analysts and policy makers lack the data they need to explain some current aspects of the economy.

The changes in the new economy since 1990 have been due primarily to the information and communications technology revolution, which has massively and fundamentally altered the capitalist economy. It has accelerated the process of globalization with the rise of global value chains, enabled nations to export production capacity instead of manufactured goods, and facilitated the transmission of ideas across national borders.

Capital – a term coined by Karl Marx in Das Capital, published in 1867, to refer to machines used to create wealth for their owners – is no longer the driving force of the new economy. It is ideas and how innovation is organized and encouraged that has become the new capital — intangible capital.

What Are Intangible Assets?

Intangible investments and assets include software, databases, scientific research, mineral prospecting, creative works, design, training, market research, brand building and business processes. Tech firms and sharing-economy companies are among the most “intangible intensive” businesses: Think of Apple’s distinctive designs or the networks that link to drivers at the heart of Uber.

Tangible assets, on the other hand, are buildings and structures, IT equipment (computer hardware, communications equipment), non-computer machinery, equipment and weapons systems, and vehicles.

In 1977, the assets of a commercial gym would consist of exercise equipment, lockers and a reception desk. In 2017, a gym’s physical assets would fall into the same categories as they did in 1970, aside from the presence of personal computers. But the gym’s business now relies on many more intangibles, such as the software that runs its computers or the design of its particular fitness classes. Today, gym owners can even buy licenses to teach classes created by a completely separate outside firm that does not own gyms or employ instructors.

Similarly, many of a modern supermarket’s resources, such as refrigerators, shopping carts and delivery trucks, resemble those of grocery stores in the past. But supermarkets now incorporate intangibles such as computer-managed supply chains, employee procedure protocols, and inventory tracking systems.

What is new about today’s economy is not the role of ideas themselves, but rather that many of our best ideas remain disembodied. The idea is indeed valuable, but it does not take physical form. This changes almost everything. Apple, the world’s most valuable company, owns virtually no physical assets. It is its intangible assets — integrating design and software into a brand — that create value.

Since 1990, intangible investment has exceeded tangible investment in the US. In the UK this changeover started in 2000. But in Continental Europe investment in tangibles still exceeds intangibles, especially in Spain, Italy and Germany.

This matters because the properties of intangibles are fundamentally different from those of tangibles. Understanding those differences may explain some of the peculiar features of the modern economy, including rising inequality and slowing productivity.

Nature of intangibles: Accounting conventions

In company and national accounts, many forms of intangible investments are unmeasured. The typical treatments of intangible investment in company accounts follow four patterns: (1) if carried in the company’s own account it is expensed, not capitalized, (2) if bought-in it is valued and depreciated, (3) if the company is sold it is valued as ‘goodwill’, and (4) some software and R&D expenditures can be capitalized under restrictive circumstances, e.g., at a late stage in development.

One of the consequences is a firm that makes large intangible investments becomes fabulously profitable in terms of its return on capital, i.e., huge sales with little capital. But if we miss out the intangible investments, we undercount GDP. Since changes in investment are early predictors of business cycles, we might also miss early signals of future output and productivity. For example, if the trade war between the US and China leads to more uncertainty and reduces investment in intangibles, then future growth will be more adversely impacted than predicted by standard economic models that do not recognize intangible investments.

The Nature of Intangibles: Economic Properties

Intangible investments can be distinguished from tangible investments in four ways:

1. Intangibles are typically “sunk investments”. A business can usually offload physical items, such as machinery, but reselling intangible assets in a secondary market is more difficult. The distinctive needs of organizations that invest in intangibles usually guide the creation of those intangibles and that customization makes them harder to resell. This also makes it harder to secure bank financing for intangibles because banks have fewer options for collateralizing them.

2. Intangibles tend to generate “spillovers” because knowledge investment is similar to what economists call non-rival investment in goods that can be used by others over and over again. Competitors can copy nonphysical investments, such as production processes, with relative ease. Companies that manage spillovers make the most of their intangibles and extract value from other firms’ ideas. Consider that Apple invented the iPhone on the back of rivals’ missteps and on the basis of state-funded research.

3. Intangibles are “scalable”. Unlike a machine or an office, a firm can use an intangible asset in many places simultaneously. For example, Starbucks can utilize a coffee-making machine in only one store at a time, but it can write one operations handbook and use it in every store. In an intangible-intensive economy, businesses that are adept at scaling — like Starbucks, Google, Microsoft and Uber — will dominate.

4. Intangibles are “synergistic”. The intangibles can interact with each other or with physical and human assets. For example, Airbnb combines its intangible assets — its network of housing hosts — with its material technologies such as computers and smartphones. Synergy acts as a counterforce to spillover: The rewards of synergy prompt collaboration, particularly through open innovation.

Business Differences

The business-related differences between tangibles and intangibles rest on several qualities:

1. Uncertainty. While all investments are uncertain, intangible investments seem more unpredictable than tangible investments. Intangibles carry more risk because if they go bad, recovering their value is difficult. But due to scalability and synergies, the upside potential of an intangible investment could be far greater than that of investing in a tangible asset.

2. Option value. Even if a firm doesn’t derive a marketable asset from its sunk costs in an intangible, it can still extract valuable information from the process that it can use for future opportunities.

3. Contestedness. Intangible assets, such as ideas, are “non-rival” goods, because many different firms can exploit them. If you own a tangible asset, competitors can’t legally enter your property and use it. Protecting ideas and knowledge is harder, because the rules associated with them are “contested.” Businesses strive to claim ownership and control of intangibles through patent and copyright laws. But intellectual property rules are often ambiguous. One outcome of contestedness is that firms seek and reward employees who are skillful at extracting proprietary value from contested ideas.

Implication of intangibles: scalability

Intangibles worsen the productivity gap between leading firms and laggards. How so?

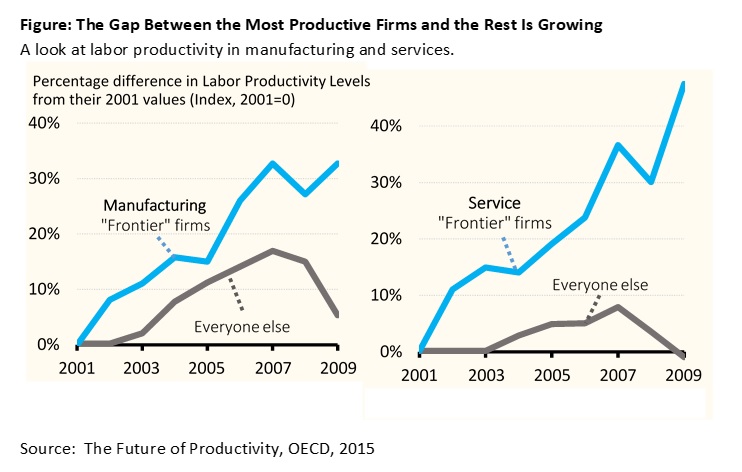

Tangible-intensive industries have constant returns to scale. The productivity gap between leading and laggard firms stays the same over time. Successful or frontier companies expand, but do not widen the productivity gap with others.

The scalability of intangible-intensive industries, however, offers promise of increasing returns to scale. Successful companies that expand become progressively more productive than less successful ones. The productivity gap widens over time between leading and laggard firms.

We can already see that the gap between the most productive firms and the rest is growing (see Figure). The percentage difference in labor productivity levels over the period 2001-09 between “frontier” firms and everyone else increased over time, more so in the service sector where intangible investments are more important.

Intangible investments are ideas that cannot be utilized by one firm without other firms learning about it. They could then copy and perhaps even enhance its economic value. Learning spreads ideas and produces spillovers. Tangible assets are unlikely to produce spillovers. If a firm buys a vehicle or a premise, it can exclude others from using it. Intangibles cannot be locked up in this way. An important implication is that a fall in intangible capital investment can result in a fall in the productivity of the industry or economy as a whole. The economic growth of a nation is therefore adversely affected.

There is also considerable evidence that frontier firms pay higher wages to all workers, both skilled and unskilled ones. To some degree this is due to the sorting of more productive workers into the frontier firms. But there is also a separate effect. Frontier firms invest more in intangibles, especially in what the economist Gary Becker called “specific human capital’, that raises the productivity of the worker in the firm making these investments but not elsewhere. However, to retain these workers the firms have to share their profits with these workers.

The result is that intangible-intensive industries with such frontier firms become more concentrated and also increase wage inequality in the labor force.

Since the opening of China and the expansion and relocation of manufacturing economic activities across the border, Hong Kong has become a totally service economy. What implications does the rising intangible economy have for our economy and public policy, especially positive non-interventionism? I shall explore these issues in my next column.

Reference

J. Haskel and S. Westlake, Capitalism Without Capital: The Rise of the Intangible Economy, Princeton University Press, 2017