(This essay was published in Hong Kong Economic Journal on 7 June 2017.)

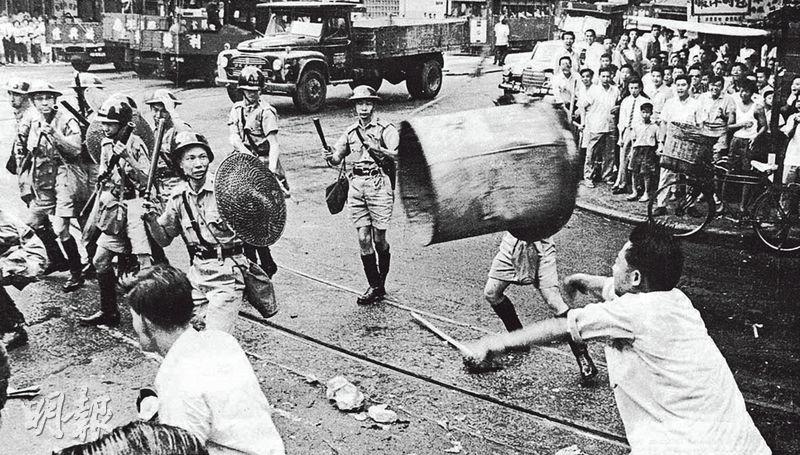

This year is the 50thAnniversary of the 1967 Riots. The riots are popularly seen as a watershed event in Hong Kong’s post-war history, but they have hardly been thoroughly researched. What follows is a narrative of housing policy choices that I believe are important distant causes of the 1967 Riots.

Housing policy in Hong Kong in the past 70 years encountered seven critical junctures that set us on paths of development leading to our present housing condition. At each of these junctures, choices were made that exerted a long-lasting impact. The three distant causes of the 1967 Riots are discussed in this article, and the unintended consequences next week.

Path dependence is the idea that history matters for current decision-making situations and has a strong influence on strategic planning. Past policy choices create institutional arrangements that appear as laws, regulations, and accepted values. They are made operational by bureaucracies, committees, and a variety of actors and agents.

Path dependence argues institutional arrangements put in place at a certain point in time become entrenched because they shape the incentives, worldviews, and resources of the actors and groups affected by the institution. When this occurs, stakeholders and constituencies defend and promote the continuation of these institutional arrangements; and in so doing they limit the choices of current and future decisions makers.

Critical junctures are an essential component of the path dependence argument. These arise when there is a moment of uncertainty about the future of an institutional arrangement that allows political actors and agents to exercise choice and play a decisive role in setting a new development that sends society on a different trajectory. The new institutional arrangement created at a critical juncture will then persist over a long period of time.

1947 Rent Control

Between 1945 and 1948 the total population in Hong Kong increased from 600,000 to 1.8 million. Nevertheless, in 1948 there were only 30,000 squatters representing 2 per cent of the population. The private sector had managed to house essentially the entire population within the existing pre-war housing stock. Even by 1953, although there were 300,000 squatters, they made up only 10 per cent of the population.

Despite the rapid and massive influx of immigrants, Hong Kong’s most important housing challenge during that time was not squatters, but cramped living conditions in existing permanent housing. Shantytowns like those in Calcutta and Mexico City were not widespread in Hong Kong and not the government’s major headache. Living conditions in these squatter units built illegally by private developers at that time were quite spacious compared to permanent tenement housing units, and more expensive.

The government’s response in October 1945 was to make an emergency proclamation to clamp down on rents on all existing pre-war premises to protect Hong Kong residents against rising rents. Discrimination against non-residents and new immigrants was intended. In May 1947 the Landlord and Tenancy Ordinance was enacted to control rent on all pre-war domestic and business premises. The rents charged were set with reference to pre-war levels, and rent increases were limited to 30 per cent of the standard rent.

The immediate effect was devastating. It has become extremely difficult to evict existing tenants and almost impossible to tear down prewar units for reconstruction into taller structures. An enormous shortage of accommodation erupted. The market could not respond to the rapidly growing demand for domestic housing and the expanding needs of industry and commerce. Rent control was a terrible policy response adopted by the British government in the face of an enormous influx of immigrants – it was a ‘Hong Kong first’ choice.

Interestingly, the British government in Singapore also introduced a rent control ordinance in 1947. Its effect was also devastating even though Singapore did not experience the same degree of population influx as Hong Kong. Still, public discontent at the housing situation was so intense that it helped the ascendance of the People’s Action Party and put Lee Kuan Yew in power on a housing platform.

Rent control was a critical juncture for housing policy choice in Hong Kong. It created an enormous pent-up demand due to a housing shortage that was accommodated by many households sharing the same unit.

1954 Resettlement Housing

By 1953, squatters had invaded most of the land surrounding the urban areas and occupied it with illegally constructed housing structures. Land available for commercial and industrial development was in short supply, which was delaying economic development. The problem was compounded by the difficulty in redeveloping prewar structures because of rent control legislation.

In 1954, the government introduced a new housing policy to relocate squatters into publicly-provided resettlement estates after clearing squatter areas for development. Although the resettlement policy took place immediately after the Shek Kip Mei fire, its inspiration was less compassion for the homeless victims than the pressing need to find new developable land.

The resettlement policy created perverse incentives for households living in crowded tenement blocks to opt to become squatters with the expectation that they, too, would be resettled in time. Surveys of squatter settlements in 1957 showed that half of them had lived in private housing before becoming squatters.

As existing squatter areas were cleared, more new ones soon appeared. The number of squatters actually increased from 300,000 in 1954 to 600,000 in 1964. Eventually more than a million squatters were resettled. The public rental housing program suddenly expanded beyond all expectations. The resettlement policy for clearing occupied land for development was the second critical juncture for housing policy choice in Hong Kong.

The government also made it clear that resettlement housing was not aimed at accommodating low-income families, but was only for resettling homeless squatters after their units were demolished and the area cleared for development. Squatters admitted into the program, therefore, did not have to be means tested. Between 1954 and 1964, a total of 126,650 public housing units were produced. Of these, the largest share, 97,349, was made up of resettlement estate units.

This sowed the seeds for discontent in society. Many honest, law-abiding, low-income households living in cramped old tenement units naturally felt aggrieved because they were losing out to opportunistic squatters, many of whom were not poor but were willing to live in illegally-built squatter units.

1962 Plot-Ratio Amendment Disaster

In 1954, Mr. John Way, who was the Chairman of the Tenancy Tribunal, was well aware of the enormous social cost of the delays in redevelopment caused by rent control. He invented the most ingenious argument and convinced the court in a landmark court case on possession and reconstruction to permit redevelopment to occur. The criterion of public interest was now reduced to the simple measure that the new building must be superior to the old one.

With the new rules in place, eviction cases declined drastically as landlord and tenant came to quick agreement. This greatly lowered the transaction costs for evicting tenants. Unfortunately, the Tenancy Tribunal at the recommendation of Mr. M. W. Lo fixed a low rate of compensation. As a consequence, redevelopment in Hong Kong took place at a breakneck pace.

The average height of buildings constructed in the period 1960-62 rose to 9.39 stories. Over-congestion became a problem as essential infrastructure lagged behind. An ad hoc plot-ratio amendment was enacted in 1962 to reduce the amount of redeveloped land space. But it had an odd loophole.

An explanatory note attached to the amendment stated that the new regulation would come into operation on 19 October 1962, but the Building Authority would be able to approve submissions for building works according to the old regulations if these were submitted at any time prior to 1 January 1966. This loophole triggered a disastrous building rush that swept through Hong Kong between 1962 and 1965.

Landlords used all means to submit building plans ahead of the deadline because this was a now-or-never decision. Tenant eviction reached enormous proportions when old congested buildings were torn down. Had all the ambitious building plans submitted in this window period carried to fruition, an unimaginable one-third to one half of the city’s buildings would have been replaced! This did not happen as the construction boom soon turned into an economic recession.

A minor run on the banks in 1964 was followed by a surge of heavier bank runs in 1965, until even the largest Chinese bank was forced into a change of ownership. The housing boom collapsed from mid-1965 until late-1969. Half-built structures stood everywhere.

The 1967 Riots occurred in the middle of this economic recession. The rush of construction triggered the bank runs and the subsequent economic recession, and the living conditions of many evicted tenants worsened . It is not difficult to conjecture how the construction rush triggered tense social and economic conditions prior to the 1967 Riots.

Indeed, economic and social discontent in Hong Kong was like a tinderbox ready to explode. The year before, in 1966, there were riots for three days following government’s decision to increase the first-class fare on the Star Ferry harbor crossing by 5 cents. Many of the rioters were young people, aged 16 to 20. They were mainly from the lower classes that would not even have purchased first-class tickets.

Such was the disastrous unintended consequences of the 1962 plot-ratio amendment. Whether this was sheer legislative folly or a product of sinister intentions is unknown.

Summary

At the first critical juncture in 1947, the government chose rent control in the face of a massive influx of immigrants. This prolonged the period of severe housing and land shortage.

At the second critical juncture in 1954, the government decided to use squatter resettlement as a means to clear occupied land for development. The public rental-housing program rapidly grew but also sowed the seeds for subsequent economic and social discontent among low-income households that were not favored by the resettlement program.

At the third critical juncture in 1962, the plot-ratio amendment disaster exacerbated economic and social discontent, especially among the low-income segments of society, and fostered the conditions for the riots that finally erupted first in 1966 and then again in 1967.

After the 1967 Riots, the government made many major policy changes. The centerpiece was to embark on a massive public rental-housing program aimed at low-income households rather than resettling squatters. This would subsequently become the source of future economic and social discontent. But that is another story – the unintended consequences of the 1967 Riots.

Photo: Ming Pao